Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common inflammatory disease of the nasal mucosa resulting from immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated reactions to specific inhaled allergens [1]. Allergens activate mast cells in the nasal mucosa, leading to histamine release, and causing AR symptoms, such as sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal itching, and congestion [2]. AR affects approximately 10-40% of the world’s population, particularly children and adolescents [3]. It has emerged as a major health concern due to its adverse impact on quality of life and productivity at work or school [4]. Nonetheless, there is currently no established cure for this disease [5]. Hence, there is a pressing need to develop more effective approaches for AR treatment.

Inflammation is a critical regulator of AR progression. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-5, IL-6, IL-13, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) have been reported in AR patients and mouse models [6]. These factors further recruit eosinophils and mast cells to the affected tissue [7]. Moreover, damaged airway epithelial cells also participate in the sensitization process via the secretion of cytokines/alarmins, including IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) [8]. Of note, IL-13 is a prototypical Th2 cytokine that functions as a key mediator in allergic inflammation-elicited pathophysiological changes and is associated with increased mucus production and release of inflammatory mediators in airway epithelial cells [9]. IL-13-stimulated human nasal epithelial cells (HNEpCs) have been used as a common cell model for AR study [10]. Moreover, oxidative stress, which results from either overproduction of reactive species oxygen (ROS) or insufficiency of the antioxidant defense system, is directly linked to chronic inflammation and plays a pivotal role in AR pathogenesis [11]. Thus, eliminating or reducing excessive inflammation and oxidative stress may be helpful for AR treatment.

Astaxanthin (AST) is a lipid-soluble carotenoid frequently found in aquatic organisms [12]. It is considered safe for food consumption and has been approved as a dietary supplement [13]. Evidence suggests that AST possesses a wide range of pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, anticancer, and neuroprotective properties [14]. Importantly, it was reported that AST could augment the activity of antihistamines to suppress lymphocyte activation in patients co-afflicted with both seasonal AR and pollen-related asthma [15]. Moreover, Hwang et al. proposed that AST attenuated airway inflammation in an asthmatic mouse model [16]. High mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) is a prototypical damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) protein and acts as an alarmin activating inflammatory and immune responses when it is translocated to the extracellular space [17]. Of note, inhibiting HMGB1 has been reported to be a promising therapeutic approach for AR patients [18]. Intriguingly, Abbaszadeh et al. demonstrated that AST suppressed HMGB1/TLR4 (Toll-like receptor 4) signaling in rats with spinal cord injury [19]. Nevertheless, the precise effect of AST on AR symptoms and the associated mechanism remain unclear.

In this study, we explored the functions of AST in AR using a mouse model and an IL-13-induced HNEpC model. We hypothesized that AST could alleviate AR symptoms by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress. The results may help develop new therapeutic strategies for AR.

Material and methods

Animals

Female BALB/c mice (6-week-old, 18-20 g) were purchased from Cavens (Changzhou, China) and housed under 12-h light/dark cycles with controlled temperature (22 ±2°C) and humidity (50-60%) and free access to food and water. All animals were given one week of acclimatization before experiments. All experimental procedures were conducted as per the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine.

Mouse AR model

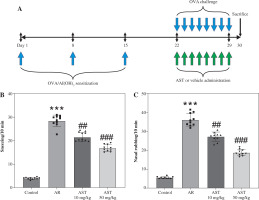

Forty mice were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 10/group): control, AR, AR + 10 mg/kg AST, and AR + 50 mg/kg AST. The mouse AR model was established by ovalbumin (OVA) induction according to previous reports [20, 21]. In brief, all mice, except those in the control group, were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 100 μg of OVA (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China) and 2 mg of aluminum hydroxide [Al(OH)3] (MedChemExpress) dissolved in 100 μl of saline on days 1, 8 and 15. Then the mice were challenged with 20 μl of OVA (40 mg/ml) daily on days 22-29 by intranasal instillation. For drug treatment, the mice were orally administered with 10 or 50 mg/kg AST (purity ≥ 98.0%; HY-B2163, MedChemExpress) dissolved in olive oil (vehicle). The control mice and untreated AR mice were given the same amount of olive oil alone. The doses of AST were determined based on previous studies [16, 22]. The control mice were administered (i.p.) with normal saline without sensitization or challenge. A schematic diagram of the experimental procedure is shown in Figure 1A.

Analysis of nasal symptoms and sample collection

Following the last OVA challenge and drug administration, mouse nasal symptoms including the frequency of sneezing and nasal rubbing were evaluated for 10 min in a blinded way. On day 30, all mice were euthanized under anesthesia by cervical dislocation. Blood was collected and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C to obtain the serum. The serum was stored at –80°C for subsequent use. Moreover, mouse nasal mucosa was collected for histologic analysis, measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels, and western blotting.

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining

Mouse nasal mucosa was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (5-μm thick). The nasal sections were deparaffined and rehydrated, followed by staining with H&E (G1120, Solarbio, Beijing, China) as per the manufacturer’s protocols. The results were observed under a microscope (Leica Microsystems, Shanghai, China). Four random fields of each section were selected for the counting of eosinophils.

Cell culture and treatment

Human primary nasal epithelial cells (HNEpCs) from WheLab (Shanghai, China) were incubated in the epithelial cell medium (M1005A, WheLab) in a humidified incubator (5% CO2, 37°C). To examine the effect of AST on allergic inflammation, HNEpCs were stimulated with 50 ng/ml IL-13 (purity ≥ 95%, ab270079, Abcam, Shanghai, China) for 24 h [23] in the presence of 20 or 50 μM AST. To inhibit TLR4 signaling transduction, cells were treated with 5 μM TAK-242 (a TLR4 inhibitor; MedChemExpress).

Fig. 1

Astaxanthin (AST) mitigates nasal symptoms in allergic rhinitis (AR) mice. A) A schematic diagram illustrating the process of mouse AR model establishment and AST administration. B, C) The number of sneezing (B) and nasal rubbing (C) in each group. n = 10. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. AR group

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

HNEpCs were inoculated in 96-well plates (5 × 103/well) and treated with various concentrations of AST (0-100 μM) for 24 h. Afterward, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was added to each well for an additional 1-h incubation. Cell viability was determined by estimating the 450 nm optical density using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay

Lactate dehydrogenase release in the culture medium was detected using an LDH Assay Kit (C0016, Beyotime). In brief, HNEpCs were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with or without IL-13 and AST for 24 h. Then, cells were centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and added (120 μl) to a clean 96-well plate, followed by a mixture with LDH reaction solution (60 μl) for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was estimated at 90 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum levels of histamine (EM1510), OVA-specific IgE (EM2035), LTC4 (EM2089), IL-5 (EM0120), IL-6 (EM0121-HS), TNF-α (EM0183), IL-25 (EM1162), IL-33 (EM0118), and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP; EM0201) were determined using mouse ELISA kits (FineTest, Wuhan, China), and the levels of IL-5 (EH0200), IL-6 (RTU-EH0201), TNF-α (EH0302), IL-25 (EH0180), IL-33 (EH0198), and TSLP (EH0322) in HNEpCs were estimated using human ELISA kits (FineTest) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of oxidative stress-related markers

The corresponding assay kits were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China) for evaluating the levels of MDA (A003-1-1) and SOD (A001-3-2) following the recommendations of the manufacturer.

Intracellular ROS level was determined using a 2,7-dichlorofuorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe (E004-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Briefly, cells were treated with a DCFH-DA fluorescent probe (20 μM) for 30 min, followed by rinsing three times with PBS. H2O2 (50 μM) was used as a positive control for ROS production. Relative ROS levels were determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of dichlorofluorescein (DCF) using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific).

Western blotting

RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime) was employed for protein extraction from mouse nasal mucosa or HNEpCs, and a BCA assay kit (Beyotime) was used for protein concentration evaluation. Protein samples were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto the polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Beyotime), followed by blocking with 5% defatted milk. The primary and secondary antibodies used in this study are shown in Table 1. Lastly, blot signals were detected using BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime), and the band intensity was estimated using ImageJ software.

Cell reporter assay

The HEK-Blue hTLR4 reporter cell line was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA) and maintained according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were seeded into 96-well plates (4 × 104 cells/well). After the mentioned treatments, supernatants were collected, and secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) released in the culture medium was quantified using QUANTI-Blue Solution (InvivoGen). SEAP activity, as an indicator of TLR4 activation, was assessed by measuring the optical density at 650 nm (OD650) with a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. Comparisons of differences among groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0.2; GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Results

AST mitigates nasal symptoms in AR mice

The mouse AR model was established by OVA induction and was administered with or without AST. The nasal symptoms, including sneezing and nasal rubbing, were estimated for 10 min in each group. As shown in Figure 1B, C, in AR mice, there was a significant increase in the frequency of sneezing and nasal rubbing. Nonetheless, AST (10 and 50 mg/kg) markedly reduced the nasal symptoms in AR mice (Fig. 1B, C).

Table 1

Primary and secondary antibodies used in western blotting

AST alleviates nasal pathological damage and inflammatory response in AR mice

H&E staining was conducted for histologic analysis of mouse nasal mucosa. The results show that the AR group exhibited significant nasal epithelium thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in comparison to the control group (Fig. 2A). In contrast, these pathological changes were prominently alleviated by AST administration (Fig. 2A). Consistently, semi-quantitative analysis showed that eosinophil numbers were significantly elevated in the AR group compared to the control group, whereas AST treatment significantly attenuated eosinophil infiltration in the nasal mucosa of AR mice (Fig. 2B). Moreover, AR is characterized by elevated release of histamine and OVA-specific IgE [5]. Our results demonstrated that the serum levels of histamine and OVA-specific IgE were prominently increased in AR mice (Fig. 2C, D), along with elevated serum levels of proinflammatory mediators, including LTC4, IL-5, IL-6, and TNF-α (Fig. 2E-H). Nevertheless, AST treatment dose-dependently counteracted the above effects in AR mice (Fig. 2C-H). Furthermore, we evaluated the serum levels of epithelial-derived cytokines (alarmins) in each group. As the results show, the serum levels of these alarmins (IL-25, IL-33, TSLP) were increased in AR mice and were decreased after AST treatment (Fig. 2I-K). Collectively, these results revealed the ameliorative effect of AST on nasal pathological damage and inflammatory response in OVA-induced AR mice.

AST relieves oxidative stress in nasal mucosa of AR mice

Evidence suggests that oxidative stress functions as a pivotal contributor to AR progression. We then measured the levels of oxidative stress-related markers (MDA, SOD, NOX2, Nrf2, HO-1) in mouse nasal mucosa. In comparison to the control mice, AR mice showed a marked increase in the level of MDA, a product of lipid peroxidation, and a decrease in the activity of SOD, a critical anti-oxidant enzyme (Fig. 3A, B), indicating that OVA elicited oxidative stress in mouse nasal mucosa. Notably, AST treatment prominently reduced MDA levels and elevated SOD activity in the nasal mucosa of AR mice (Fig. 3A, B), suggesting the antioxidant role of AST. Furthermore, as displayed by western blotting, AST administration remarkably abated OVA-triggered upregulation of NOX2 (NADPH oxidase 2) as well as downregulation of Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) and HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1), two important antioxidant proteins in mouse nasal mucosa (Fig. 3C, D). Taken together, the above results demonstrated that AST could attenuate OVA-evoked oxidative stress in AR mice.

Fig. 2

Astaxanthin (AST) alleviates nasal pathological damage and inflammatory response in allergic rhinitis (AR) mice. A) Representative images of H©E staining showing the histological changes of mouse nasal mucosa in each group. B) Quantification of eosinophil number from H&E staining. n = 5. C-E) ELISA for determining serum levels of histamine (C), OVA-specific IgE (D), LTC4 (E) IL-5 (F), IL-6 (G), TNF-α (H), IL-25 (I), IL-33 (J), and TSLP (K) in each group. n = 10. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. AR group

Fig. 3

Astaxanthin (AST) relieves oxidative stress in the nasal mucosa of allergic rhinitis (AR) mice. A, B) Measurement of MDA level (A) and SOD activity (B) in mouse nasal mucosa. n = 5. C) Representative images of western blotting depicting protein levels of NOX2, Nrf2, and HO-1 in mouse nasal mucosa. D) Quantitative results of western blotting. n = 5. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. AR group

Fig. 4

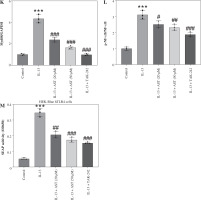

Astaxanthin (AST) blocks HMGB1/TLR4 signaling transduction in allergic rhinitis (AR) mice and IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs. A) Representative images of western blotting showing HMGB1, TLR4, Myd88, and (p-) NF-κB protein expression in mouse nasal mucosa. B-E) Quantification of protein levels in mouse nasal mucosa. n = 5; ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. AR group or IL-13 group F) CCK-8 assay showing changes in HNEpC viability following treatment with different concentrations of AST (0-100 μM) for 24 h. G) CCK-8 assay showing the viability of HNEpCs treated with or without IL-13 and AST. H) Western blotting of HMGB1 protein level in HNEpCs. I) Representative images of western blotting showing HMGB1, TLR4, Myd88, and (p-) NF-κB protein expression in HNEpCs. J) Quantification of protein levels in HNEpCs. n = 3. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. AR group or IL-13 group K, L) Quantification of protein levels in HNEpCs. M) Evaluation of SEAP activity in the culture medium n = 3. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. AR group or IL-13 group

AST blocks HMGB1/TLR4 signaling transduction in AR mice and IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs

Considering the critical role of the HMGB1/TLR4 (high mobility group box-1/Toll-like receptor 4) signaling pathway in AR and the regulatory effect of AST on this pathway, we assessed whether AST could affect this pathway in AR by evaluating the associated protein levels in mouse nasal mucosa and HNEpCs. Notably, AR mice exhibited much higher levels of HMGB1, TLR4, Myd88, and phosphorylated (p)-NF-κB than the control mice (Fig. 4A-E), suggesting the activation of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling in the nasal mucosa of AR mice. Nonetheless, AST administration dose-dependently impeded HMGB1, TLR4, and Myd88 protein expression and suppressed NF-κB phosphorylation in the nasal mucosa of AR mice (Fig. 4A-E). To better understand the protective role of AST in AR, we established an in vitro AR model by stimulating HNEpCs with IL-13. To obtain an optimal dose of AST, HNEpCs were treated with various doses of AST (0-100 μM) for 24 h, followed by assessing cell viability using the CCK-8 assay. As the results show, AST at a concentration below 100 μM had no significant cytotoxicity towards HNEpCs (Fig. 4F). Thus, 20 and 50 μM AST were selected for follow-up experiments. CCK-8 assay showed that IL-13 stimulation significantly impaired HNEpC viability, which was dose-dependently rescued by AST treatment (Fig. 4G). Consistent with the above animal experiments, the in vitro results demonstrated that AST reduced the protein levels of HMGB1, TLR4, Myd88, and p-NF-κB in IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs (Fig. 4H-L). Of note, the effect of AST (50 μM) was similar to that of TAK-242, a selective TLR4 inhibitor (Fig. 4I-L). Furthermore, we used a commercially engineered TLR4 reporter cell line (HEK-Blue hTLR4) designed to study the stimulation of TLR4 by monitoring the activation of NF-κB. NF-κB activation induces the production and secretion of SEAP, which can be detected in the culture medium. Notably, IL-13 stimulation induced the release of SEAP in the culture medium, while this effect was reversed by AST or TAK-242 treatment (Fig. 4M). The above results indicated that AST could block HMGB1/TLR4 signaling transduction in both AR mouse nasal mucosa and IL-13-treated HNEpCs.

AST ameliorates inflammation and oxidative stress in IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs

As shown in Figure 5A, IL-13 significantly stimulated LDH release in the culture medium, whereas AST or TAK-242 treatment abated this effect, indicating that AST attenuated IL-13-triggered cell injury. Consistent with the in vivo results, ELISA revealed that AST or TAK-242 treatment counteracted IL-13-induced elevation of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, TNF-α) and alarmins (IL-25, IL-33, TSLP) in HNEpCs (Fig. 5B-G). Moreover, ROS and MDA levels were enhanced, and SOD activity was weakened in IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs, while these conditions were partially reversed by AST treatment in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5H-J). Additionally, AST, especially the higher concentration (50 μM), showed similar effects to the TLR4 inhibitor TAK-242 (Fig. 5H-J). These data demonstrated that AST could ameliorate IL-13-triggered dysfunction of HNEpCs in vitro by inactivating the HMGB1/TLR4 signaling pathway.

Discussion

The present study revealed that AST treatment significantly ameliorated nasal symptoms, attenuated nasal mucosa pathological damage, and reduced inflammation and oxidative stress in OVA-induced AR mice. Moreover, AST could attenuate the IL-13-triggered inflammatory response and oxidative stress in HNEpCs. Mechanistically, the protective effect of AST might be associated with inhibition of the HMGB1/TLR4 signaling pathway.

AR is characterized by typical symptoms and increased levels of histamine as well as allergen-specific IgE [24]. The OVA-induced AR model is widely used in the studies of this disease. OVA-triggered systemic sensitization with the subsequent intranasal challenge mimics the clinical characteristics of IgE-mediated allergic inflammation [25]. Consistent with previous studies, our results demonstrated that OVA induced allergic symptoms, including sneezing and rubbing, and elicited pathological damage to the nasal mucosa of mice. However, AST administration could markedly mitigate these allergic symptoms in mice with AR. In response to allergens, mast cells are activated and release large amounts of histamine, which is responsible for inflammatory cell infiltration to the nasal mucosa and related symptoms [26]. The present study showed that serum levels of histamine and OVA-specific IgE were elevated after the intranasal OVA challenge, along with the elevated levels of inflammatory mediators, including LTC4, IL-5, IL-6, TNF-α. IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP. However, these conditions were prominently counteracted by AST administration. Furthermore, we also found that AST treatment reduced inflammatory cytokine production in IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs. Previous evidence demonstrated that AST reduced total IgE in the serum and IL-5 production in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of asthmatic mice [16]. Moreover, Xie et al. reported that AST impeded IL-6 and TNF-α expression in lipopolysaccharide-induced human periodontal ligament cells [27], which supports our findings in this study.

Mounting evidence has suggested that oxidative stress acts as a critical mediator in the pathogenesis of AR [28]. NOX2 is a primary source of ROS. Excessive ROS leads to tissue damage and aggravates the inflammatory response [29]. Previous reports have revealed that AST can suppress oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway [30]. Consistently, we found that AST treatment attenuated oxidative stress in the nasal mucosa of AR mice by reducing MDA and NOX2 and elevating the antioxidant proteins Nrf2, HO-1, and SOD. The antioxidant activity of AST was also confirmed in IL-13-treated HNEpCs. Previous evidence has indicated that AST is an antioxidant [31], which explains the observed reduction in oxidative stress following AST treatment.

Studies have identified HMGB1 as a promising therapeutic target for AR, and elevated HMGB1 levels have been observed in nasal secretions from AR patients [18]. TLR4 is a primary receptor of HMGB1 and is involved in inducing cytokine production. Myd88 serves as a downstream adaptor protein of TLR4 and can activate and regulate NF-κB signaling [32]. Of note, it was proposed that AST could hinder HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling transduction, thereby alleviating edema and inflammation in mice with spinal cord injury [19]. Similarly, our results showed that AST blocked the HMGB1/TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB pathway in the nasal mucosa of AR mice and in IL-13-treated HNEpCs. Additionally, the above effects of AST were similar to those of a pharmacological inhibitor of TLR4 (TAK-242), suggesting that the protective effect of AST on AR might be associated with inhibition of HMGB1/TLR4/Myd88 signaling transduction.

Fig. 5

Astaxanthin (AST) ameliorates inflammation and oxidative stress in IL-13-stimulated HNEpCs. A) Detection of LDH release in the culture medium of HNEpCs treated with/without IL-13, AST (20 or 50 μM), or TAK-242 (a TLR4 inhibitor). B-D) ELISA for determining levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, TNF-α) in HNEpCs with indicated treatments. n = 3. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. IL-13 group E-G) ELISA for determining levels of alarmins (IL-25, IL-33, TSLP) in HNEpCs with indicated treatments. H-J) Measurement of ROS, MDA, and SOD levels in HNEpCs of each group. n = 3. ***p < 0.001 vs. control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. IL-13 group

In conclusion, this study revealed that AST can ameliorate AR progression by reducing the inflammatory response and oxidative stress via suppression of HMGB1/TLR4 signaling. The findings may provide new ideas for treating AR patients. Additionally, future studies are required to clarify our findings and further explore the mechanisms underlying the protective function of AST in AR.