Introduction

Mucus hypersecretion is a well-known symptom of respiratory diseases, occurring in both acute infections and chronic inflammatory conditions [1, 2]. Overproduction of mucin impedes the lumen of the respiratory tract and limits optimal airflow. Furthermore, excessive mucins cause ciliary dysfunction that decreases respiratory clearance, potentially triggering various inflammatory pathways [3]. Mucin production, including mucin gene transcription, protein translation and secretion, has been studied extensively in recent years [4]. In some pathological conditions, rapid mucin secretion is often observed. The secretion process is related to the cytoskeleton and the increase in exocytosis sites, but the movement of secretion molecules and how exocytosis sites increase remain unclear.

The cell cortex is a transparent area approximately 3-5 μm thick that is underneath and closely connected with the plasma membrane. The cortex is formed by actin microfilament binding proteins and represents a dense network of actin filaments, and the fluidity of membrane proteins is restricted to some extent [5, 6]. Since the cell cortex structure is quite dense, the pore size is only 0.1 nm, and all organelles and macromolecules, including secretory granules, cannot pass through it. Therefore, how secretory granules pass through this dense structure and the molecular mechanism of the directional displacement of secretory granules guided by F-actin remain unclear. The cell cortex together with its associated membrane is the most active structure in most of the polar distributed cells. Molecular signaling is transduced successively in the cortex. Cortactin is a cortical actin crosslinking protein that exists widely in polarized epithelial cells and fibroblasts in cortical cells and in aortic smooth muscle cells [7]. Cortactin may interact with the cytoskeleton and affect the fluidity of the membrane. Additionally, it may regulate actin dynamics and participate in exocytosis, cell permeability, cell migration, and invasion [8, 9]. Our previous study showed that cortactin may be involved in the mucus secretion process by affecting F-actin polarization [10]. However, the role of cortactin in mucin secretion has not been fully elucidated.

Neutrophil elastase (NE) is a serine protease predominantly found in neutrophils. It plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of airway inflammatory diseases and regulates airway mucus secretion [11]. NE can directly act on airway epithelial cells, increasing the expression of mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and promote mucus hypersecretion by inducing goblet cell differentiation and altering the properties of mucus [12]. Recent studies have demonstrated that as a prevalent irritant responsible for mucus hypersecretion, NE is notably more stable than other irritants [13]. The mechanism by which NE promotes increased mucus secretion is not yet fully understood, and it remains unclear whether cortactin plays a role in this process.

Myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) is a crucial substrate of protein kinase C, found in all eukaryotic cells, and its function is contingent upon autophosphorylation [14]. Recent studies have shown that MARCKS is associated with various actin-dependent cellular processes, including adhesion, migration, and exocytosis [15-17]. Several studies have demonstrated that MARCKS regulates mucus secretion in airway cells, but the underlying mechanisms require further investigation [18, 19]. Therefore, we speculate that MARCKS may regulate cortactin, the cortical actin protein, thereby controlling mucus secretion. In addition, activated CDC42 kinase 1 (ACK1) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase as well as a serine/threonine protein kinase that plays a crucial role in regulating cell morphology, migration and proliferation [20, 21]. Some studies have shown that ACK1 phosphorylation may directly control actin polymerization and endocytic trafficking [22, 23]. However, the regulatory role of ACK1 in actin proteins related to mucus secretion necessitates further investigation.

In this study, we investigated the interaction of MARCKS and cortactin in regulating mucin secretion in human airway epithelial cells. We used NE as an inducer of mucus secretion. MARCKS and ACK1 were shown to enhance the phosphorylation of cortactin, promoting MUC5AC secretion in airway epithelial cells. Our study establishes a unique role for MARCKS and ACK1 in regulating mucin secretion by interacting with cortactin.

Material and methods

Materials

DMEM/Ham’s F12 medium, HEPES, fetal bovine serum (FBS), mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody, Lipo- fectamine 2000 Reagent and Opti-MEM reduced serum medium were purchased from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA). Protein A/G PLUS-agarose immunoprecipitation reagent and FITC-conjugated fluorescent secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit anti-MARCKS monoclonal anti- body was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA). Rabbit anti-p-cortactin polyclonal antibody and rabbit anti-p-MARCKS polyclonal antibody were purchased from Affinity (OH, USA). Rabbit anti-cortactin monoclonal antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody were purchased from Boster (Wuhan, China), and NE was purchased from Merck (Kenilworth NJ, USA).

Tissues

Human lung tissues were obtained from surgical specimens resected at the Department of Thoracic Surgery of the First Affiliated Hospital (Hainan Medical University) between 2017 and 2019. The experiments were approved by the institutional ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained prior to sampling. The subjects consisted of 12 patients (5 men, 7 women) aged 36-75 years. At the time of surgery, 5 patients were suffering from mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, and 7 patients had no underlying airway chronic inflammatory diseases. The tissues were examined by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining to confirm that they were noncancerous. Human bronchi for immunohistochemistry were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C for further use.

Cell culture and treatment

Human airway epithelial cells (16HBE14o-) were cultured and separately plated in a six-well plate at 5 × 105- 6 × 105 cells per well and cultured in 2 ml of DMEM/Ham’s F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The medium was replaced with growth factor-free medium (Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium) before experimental assays were conducted. The cells were treated with different concentrations of NE (0, 25, 50, 100 ng/ml) for 24 h or transfected with siRNA. Cell supernatants and lysates were collected and assayed as described below, using Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium.

SiRNA transfection

SiRNA sequences were designed and verified by qPCR and synthesized by Biofavor Biotech (Wuhan, China). Cells were transfected with cortactin (CTTN) siRNA, MARCKS siRNA, or ACK1 siRNA to investigate the role of cortactin, MARCKS or ACK1. The cells were incubated at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/ml in 24-well plates and cultured with 0.45 ml of serum free Opti-MEM in each well. Lipofectamine 2000 (5 μl) was diluted with 100 μl of serum-free medium to reach a final volume of 100 μl. Aliquots (20 μM) of MARCKS siRNA, ACK1 siRNA or control siRNA were diluted with 100 μl of serum-free medium. Subsequently, the diluted siRNA and transfection reagent were mixed and incubated for an additional 20 min at room temperature. Two hundred microliters of transfection mixture was added dropwise to each well and vortexed gently for 10 s, followed by incubation at room temperature for 6 h. After careful removal of the supernatant, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS and subsequently incubated with fresh Opti-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 h prior to further treatments. Sequence for siRNA CTTN (cortactin): forward 5′-GGAGAAAUUGCAGCUGCAUTT-3′, reverse 5′-UUGUCGAUACCGUAUUUGCTT-3′; siRNA MARCKS: forward 5′-GCGAACGGACAGGAGAAUGTT-3′, reverse 5′-CAUUCUCCUGUCCGUUCGCTT-3′; siRNA ACK1: forward 5′-GCAAGUCGUGGAUGAGUAATT-3′, reverse 5′-UUACUCAUCCACGACUUGCTT-3′.

ELISAs for MUC5AC protein

MUC5AC protein levels in the supernatant and cell lysates were measured using a Human MUC5AC (Mucin 5 Subtype AC) ELISA Kit (Elabscience, Wuhan, China). Supernatants or cell lysates were prepared with PBS at multiple dilutions. The enzyme plates were coated with 100 μl of each sample and incubated at 37°C for 90 min. The plates were washed 5 times with PBS, 100 μl of biotinylated antibody working solution was added to each well (prepared within 20 min before use), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then washed 5 times, shaken and patted on absorbent paper until dry. Then, 100 μl of enzyme binding working solution was added to each well (prepared within 20 min before use, placed in the dark), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then washed 5 times. Then, 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added and incubated at 37°C in the dark for 15 min. Then, 50 μl of stop solution was added to stop the reaction. The optical density (OD) value was read at 450 nm with an enzyme reader (Flexstation3, Molecular Devices).

Immunohistochemistry

The localization of cortactin was examined using immunohistochemical staining with an antibody against cortactin in frozen sections of human bronchi. Six-micrometer-thick sections were cut and mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides. Tissue slides were incubated with anti-cortactin antibody, anti-p-cortactin antibody or MARCKS antibody (all in 1 : 500 dilution) at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated with goat-anti mouse antibody or goat-anti rabbit antibody (1 : 500 dilution) for 30 min and streptavidin-peroxidase complex (1 : 100 dilution) for another 45 min. Then, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used as a chromogen. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used as a negative control. Epithelial cells staining positively for cortactin were counted and expressed as a percentage of the total number of epithelial cells.

Co-immunofluorescence for cortactin and MARCKS, p-cortactin and F-actin

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Then, the cells were rinsed, blocked in 1% BSA plus 1% normal goat serum and incubated with rabbit anti-p-cortactin (Tyr421) polyclonal antibody (1 : 100, Affinity) and mouse anti-F-actin monoclonal antibody (1 : 100, Abcam) in sequence overnight at 4°C. After three 3-min washes in PBST, slides were incubated with Cy3-conjugated fluorescent goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1 : 100, Boster) and FITC-conjugated fluorescent goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1 : 100, Boster) in sequence for 1 h at 37°C. After PBST washes for 3 min, the slides were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. For co-immunofluorescence for cortactin and MARCKS, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-cortactin monoclonal antibody (1 : 100, Abcam) and mouse anti- MARCKS monoclonal antibody (1 : 100, CST), respectively, and then incubated with Cy3-conjugated fluorescent goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1 : 100) and FITC-conjugated fluorescent goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1 : 100) for 1 h at 37°C. The samples were examined with an Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope.

Immunofluorescence for p-MARCKS and p-ACK1

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Then, the cells were rinsed, blocked in 1% BSA plus 1% normal goat serum and incubated with rabbit polyclonal to MARCKS (phospho S162) antibody (1 : 100, Abcam) or rabbit polyclonal to ACK1 (phospho Y284) (1 : 100, Abcam) antibody overnight at 4°C. After three 3-min washes in PBST, slides were incubated with Cy3-conjugated fluorescent secondary antibody (1 : 100) for 1 h at 37°C. After the staining procedure, the immunofluorescence was visualized using an Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope.

Western blots for detecting cortactin, MARCKS, p-cortactin, p-MARCKS, and pACK1 protein

Cells were lysed on ice in lysis buffer containing PMSF before centrifugation. Total protein was determined by a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, Beijing, China). Forty micrograms of protein from each group was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE (Beyotime) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (0.45 μm, Millipore). After the PVDF membrane was blocked with TBST with 5% skim milk powder (phosphorylated protein was blocked with 1% BSA), it was probed with anti-MARCKS antibody (1 : 800, Cell Signaling), anti-p-MARCKS antibody (1 : 800, Affinity), anti-cortactin antibody (1 : 1000, Abcam), anti-pTyr421-cortactin antibody (1 : 1000, Affinity), anti-p-ACK1 antibody (1 : 1000, Affinity), or anti- GAPDH antibody (1 : 1000, Goodhere, Hangzhou, China) as a loading control at 4°C overnight and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1 : 1000, Boster, Wuhan, China) at 37°C for 2 h. The protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence using BandScan.

Immunoprecipitation

The hCTTN-N-Myc-OE and ACK1-N-EGFP-OE plasmids were constructed using the seamless cloning strategy. Primers for cortactin (hCTTN): 5′-TTGGTACCGAGCTCGccaccatggaacaaaaactcatctcag-3′, 5′-GATATCTGCAGAATTctcacgggcactccgggacccaag-3′. ACK1: 5′-GACGAGCTGTACAAGctcacgggcactccgggacccagg-3′, 5′-GTCGACTGCAGAATTctcagcgcttgtggtgggcag-3′. After cotransfection, the cells were lysed on ice for 10-15 min and collected after full lysis. Using the Bradford method for protein quantification, we collected 500 mg of protein and adjusted the volume to 500 μl with precooled PBS. (The remaining protein was used as a western blot input control.) Agarose protein A + G beads were mixed, washed twice with precooled PBS at 3000 rpm for 5 min and then prepared to a 50% concentration with precooled PBS. Agarose protein A + G was divided into two parts, one for removing nonspecific binding and the other for binding antibody. The samples were pretreated with agarose A + G, and 50 μl of agarose A + G (50%) was added to each tube (to eliminate nonspecific binding and reduce the background). The samples were slowly rotated at 4°C for 2 h and then 3000 rpm for 5 min to remove protein A + G beads. The supernatant was collected. Then, 4 μg of Myc antibody was added to 500 μl of total protein and reacted with the target protein. The mixture was shaken slowly at 4°C overnight. Fifty microliters of 50% agarose protein A + G (30 μl/tube) was added, and the reaction was performed at 4°C for 3-6 h. Then, the mixture was vortexed at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The precipitates were washed with precooled PBS 3 times. The precipitate was suspended in 50 μl of loading buffer, boiled for 5 min, placed on ice immediately, cooled to room temperature, and vortexed at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and 30 μl was used for loading. GFP and Myc were detected by western blotting with input as a control.

Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 23. All experiments were performed with at least 3 cell cultures. Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA (followed by LSD analysis) was used to compare two or more groups. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Cortactin and MARCKS expression in human bronchial epithelium and 16HBE14o- cells

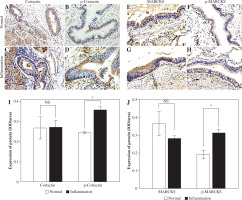

We chose specimens from individuals who had chronic inflammation, including chronic bronchitis, COPD or asthma, and used normal bronchus as a control to detect the expression of cortactin and MARCKS by immunohistochemistry. Cortactin and phosphorylated cortactin were expressed both in the normal and inflammation groups, and phosphorylated cortactin was obviously highly expressed in the airway epithelium with chronic inflammation and was mainly located in the subepithelial membrane (Fig. 1A-D, I). MARCKS was detected at the epithelial cell brush border in both the noninflammation and inflammation groups, and phosphorylation of MARCKS was significantly greater in epithelium with inflammation (Fig. 1E-H, J).

Since both MARCKS and cortactin have been individually shown to regulate F-actin relocation, we investigated whether both proteins localized in airway epithelial cells. We treated 16HBE14o- cells with NE. The colocalization of cortactin and MARCKS was assayed by coimmunofluorescence. Immunofluorescence assays showed coexpression of MARCKS and cortactin in both the normal control cells and the NE-stimulated cells. In the cells without stimulation, MARCKS was mainly expressed at the cell membrane. After NE stimulation, the overall fluorescence intensity did not show a significant change, but increased MARCKS was translocated from the cell membrane to the cytosol, and more cortactin was detected in the cell membrane, showing a polar distribution (Fig. 2A, B).

NE promotes MARCKS phosphorylation, cortactin phosphorylation, actin polarization, and ACK1 phosphorylation

The 16HBE14o- cells were incubated with different doses of NE (0, 25, 50, 100 ng/ml). Western blot analysis revealed that total cortactin and MARCKS protein levels did not show significant changes in cells. Phosphorylated cortactin (pTyr421-cortactin) and p-MARCKS protein levels increased with rising NE concentration (Fig. 2C, D). Immunofluorescence assays indicated that NE promotes the rearrangement of actin and cortactin phosphorylation, mainly at the cell membrane, and F-actin colocalizes with p-cortactin (Suppl. Fig. 1). NE also promoted MARCKS phosphorylation and induced MARCKS translocation from the plasma membrane to the cytosol (Suppl. Fig. 2).

Fig. 1

Expression of cortactin, p-cortactin, myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) and p-MARCKS in human airway epithelium. A) Cortactin expression in the noninflammation group; B) p-Cortactin in the noninflammation group; C) Cortactin expression in the inflammation group; D) p-cortactin expression in the inflammation group; E) MARCKS expression in the noninflammation group; F) p-MARCKS expression in the noninflammation group; G) MARCKS expression in the inflammation group; H) p-MARCKS expression in the inflammation group; I) Relative expression of cortactin and p-cortactin in different groups; J) Relative expression of MARCKS and p-MARCKS in different groups. An independent samples t-test was conducted for the statistical analysis, and data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. NS – no significance, *p < 0.05

To investigate whether ACK1 participates in NE-induced responses, we assayed the expression of phosphorylated ACK1 (p-ACK1) protein by immunofluorescence. The results showed that the immunofluorescence intensity of p-ACK1 increased after NE treatment in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that ACK1 may have a potential role in this process (Suppl. Fig. 3).

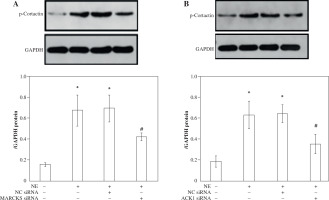

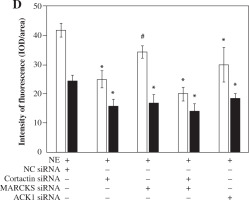

MARCKS and ACK1 knockdown decreases cortactin phosphorylation and translocation, whereas cortactin does not affect the phosphorylation of MARCKS

To assess the effect of MARCKS and ACK1 on cortactin, we transfected cells with MARCKS siRNA, ACK1 siRNA, and cortactin siRNA. The expression of p-cortactin was determined by western blotting and immunofluorescence. MARCKS and ACK1 knockdown reduced the phosphorylation of cortactin and decreased F-actin arrangement (Fig. 3A-D), indicating the important effect of MARCKS on ACK1 in NE-modulated cytoskeletal reorganization. To investigate the effect of cortactin on MARCKS expression, we assayed the expression of p-MARCKS after cortactin siRNA transfection. However, the phosphorylation of MARCKS did not show a significant change compared with that of the control group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2

Co-expression of cortactin and myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) in 16HBE14o- cells after neutrophil elastase (NE) stimulation. The long arrow indicates the membrane location of MARCKS, and the short arrow indicates the polar distribution of cortactin in the cell membrane. Scale bar = 40 μm. B) The intensity of fluorescence of cortactin and MARCKS protein expression in normal control group and NE-treated group. An independent samples t-test was conducted for the statistical analysis, and data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. NS – no significance. C) Cortactin and MARCKS protein expression after NE stimulation. 16HBE14o- cells were treated with NE (0, 25, 50, 100 ng/ml), cortactin, phosphorylated (p)-cortactin, MARCKS and p-MARCKS were assayed by western blotting. The group of blots were cropped from different parts of the same gel. D) Relative expression of MARCKS, p-MARCKS, cortactin and p-cortactin in different groups. An independent samples t-test was conducted for the statistical analysis, and data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.01, #p < 0.001 vs. untreated group

MARCKS regulates ACK1 activity

To further explore whether ACK1 is the kinase responsible for cortactin tyrosine phosphorylation, we transfected cells with ACK1 siRNA or MARCKS siRNA, and phosphorylation of ACK1 and cortactin was assayed by western blot and immunofluorescence. The results showed that NE induced ACK1 Tyr284 expression, and knockdown of MARCKS by siRNA reduced pTyr284 ACK1 expression (Fig. 5A-C), indicating that MARCKS may affect cortactin activation by regulating ACK1 activity.

ACK1 binds to cortactin and is responsible for cortactin tyrosine phosphorylation and translocation

To determine the role of ACK1 in the activation of cortactin, we cotransfected cells with GFP-tagged ACK1 (to enhance ACK1 detection) and Myc-tagged cortactin. The binding of ACK1 and cortactin was assayed by coimmunoprecipitation. GFP-ACK1 precipitated with endogenous cortactin (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the two proteins interact with each other. The immunoprecipitation was specific, since beads lacking anti-cortactin antibody did not precipitate GFP-ACK1 (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 3

Expression of p-cortactin and F-actin after myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) and activated CDC42 kinase 1 (ACK1) siRNA transfection. A) p-Cortactin expression after MARCKS siRNA transfection. *p < 0.01 vs. untreated group. #p < 0.01 vs. neutrophil elastase (NE)-treated group. p-Cort – p-cortactin. B) p-Cortactin expression after ACK1 siRNA transfection. *p < 0.01 vs. untreated group, #p < 0.01 vs. NE-treated group. The blots shown were cropped from different parts of the same gel C) Co-immunofluorescence assay of p-cortactin and F-actin. Cells were transfected with cortactin siRNA, MARCKS siRNA and ACK1 siRNA, and NC siRNA was used as a control. Colocalization of p-cortactin and F-actin was detected by immunofluorescence D) Intensity of fluorescence of p-cortactin and F-actin expression in different siRNA-transfected groups. An independent samples t-test was conducted for the statistical analysis, and data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.01, #p < 0.001

Knockdown of MARCKS and cortactin by siRNA inhibits MUC5AC secretion

To determine the role of MARCKS and cortactin in MUC5AC secretion, we transfected cells with cortactin siRNA and MARCKS siRNA before NE stimulation, and MUC5AC protein expression was detected by ELISAs. The results showed that MUC5AC protein expression was attenuated in both the cortactin siRNA- and MARCKS siRNA-transfected groups. These results showed that both cortactin and MARCKS are involved in MUC5AC secretion, with a decrease in F-actin arrangement and translocation (Fig. 3 and Fig. 6B, C).

Discussion

In this study, we found that NE promoted F-actin rearrangement and MUC5AC production in 16HBE14o- cells, with phosphorylation of cortactin and MARCKS. Inhibition of both cortactin and MARCKS by siRNA silencing effectively suppressed F-actin translocation and MUC5AC secretion. Importantly, NE also induced p-ACK1 expression in a dose-dependent manner. SiRNA-mediated knockdown of MARCKS or ACK1 attenuated p-ACK1 expression and cortactin Tyr421 phosphorylation and disrupted actin fiber rearrangement. Furthermore, we used co-immunoprecipitation to demonstrate that cortactin interacted with ACK1. Thus, this study suggests that both cortactin and MARCKS are critical modulators of actin filament formation and mucin production in airway epithelial cells. Both MARCKS and ACK1 may be important regulators of the activation of cortactin.

Mucus hypersecretion is a prominent manifestation during chronic inflammatory diseases and infectious diseases, including COPD, asthma, pneumonia, and even SARS-CoV-2 infection [24, 25]. Excessive mucin is conducive to airflow obstruction, bacterial infection, and colonization [26, 27]. Therefore, targeting mucus hypersecretion is an effective treatment strategy to improve the mortality and morbidity of these airway diseases.

The regulation of airway mucus secretion was reported to be mediated by the phosphorylation of MARCKS, which is shifted from the membrane to the cytoplasm and stabilizes adhesion to the granular membrane after dephosphorylation [28]. MARCKS is a highly conserved membrane-associated protein involved in the structural modulation of actin cytoskeleton chemotaxis, cell adhesion, phagocytosis, and exocytosis [29]. MARCKS is combined with F-actin or myosin and links mucin particles to cytoskeletal proteins such as F-actin [30]. F-actin moves the mucin particles to the cell membrane and forms a soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptor complex through exocytosis, mediates the fusion of the secretory vesicle membrane and the cell membrane, and then releases the intracellular mucin particles out of the cell [31, 32].

Here, we observed that NE stimulated MARCKS phosphorylation and F-actin arrangement in cell plasma, with increasing production of MUC5AC, consistent with previous findings [33]. Knockdown of MARCKS by siRNA interference could disturb the arrangement of F-actin and decrease MUC5AC secretion, and the phosphorylation and translocation of cortactin were also reduced, indicating that MARCKS could affect the function of cortactin. Although both MARCKS and cortactin are critical for regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, exactly how MARCKS and cortactin interact to regulate the exocytotic release of mucin in airways has not been extensively elucidated. Therefore, in this study, we further investigated the interaction between these molecules.

Cortactin is a cortical binding protein that is widely involved in cell migration and invadopodia [34]. Cortactin also facilitates the neurosecretory process, and it can regulate exocytosis via a mechanism independent of actin polymerization in chromaffin cells [35]. Recent studies have reported that cortactin is involved in many functional changes, including inflammatory responses, bronchoconstriction, alveolar disruption with increased permeability, and airway secretion [36, 37]. This molecule is associated with several important lung diseases, including COPD, asthma, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory syndrome, and acute lung injury [7, 38]. Tyr421-phosphorylated cortactin facilitates the accumulation of actin-regulatory protein profilin-1 at cell edges, promotes actin polymerization and cell movement, and plays a pivotal role in inducing smooth muscle contraction and airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma [39, 40]. However, whether cortactin participates in airway mucin secretion has not been fully elucidated.

Fig. 4

Immunofluorescence assay of p-MARCKS. A) 16HBE14o- cells were transfected with cortactin siRNA and myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) siRNA, and NC siRNA was used as a control. p-MARCKS in each group was detected by immunofluorescence. Scale bar = 50 μm. B) Intensity of fluorescence of p-MARCKS expression in different siRNA-transfected groups. An independent samples t-test was conducted for the statistical analysis, and data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.01 vs. NC siRNA-transfected group

Fig. 5

Expression of p-ACK1 after myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) siRNA transfection. A) Phosphorylated activated CDC42 kinase 1 (ACK1) protein expression detected by western blot assay after MARCKS siRNA transfection. *p < 0.01 vs. negative control group, #p < 0.01 vs. neutrophil elastase (NE)-treated group and NE + NC siRNA-transfected group. The blots shown were cropped from different parts of the same gel. B) Immunofluorescence assay of p-ACK1. Cells were transfected with MARCKS siRNA and ACK1 siRNA, and NC siRNA was used as a control. p-ACK1 was detected by immunofluorescence. Scale bar = 50 μm. C) The intensity of fluorescence of p-ACK1 expression in different siRNA-transfected groups. An independent samples t-test was conducted for the statistical analysis, and data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.01 vs. NC siRNA-transfected group

Fig. 6

A) Immunoprecipitation assay of cortactin and activated CDC42 kinase 1 (ACK1). Cells were cotransfected with Myc-cortactin and GFP-ACK1 or transfected with Myc-cortactin only. Myc was used to immunoprecipitate the specific ACK1-cortacin complex. Different groups of samples were immunoblotted with rabbit anti- Myc antibody or rabbit anti-GFP antibody. IP – Immunoprecipitation with an antibody specific to the Myc tag, used to isolate Myc-tagged proteins. IB – Myc-cortactin approximately 85 kDa; IB – GFP-ACK1 approximately 140 kDa. B) Secretion of MUC5AC protein in cell super-natants. MUC5AC protein after NE stimulation. Cells were treated with different concentrations of neutrophil elastase (NE; 0, 25, 50, 100 ng/ml), and the secretion of MUC5AC was assayed by ELISAs. *p < 0.01 vs. untreated group; #p < 0.01 vs. 25 ng/ml group. C) MUC5AC protein expression after cortactin and MARCKS knockdown. Cells were treated with 100 ng/ml NE after siRNA transfection. Secretion of MUC5AC was assayed by ELISAs. *p < 0.01 vs. untreated group, #p < 0.01 vs. NC siRNA-transfected group, &p < 0.01 vs. cortactin siRAN-transfected group and myristoylated alanine rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) siRNA-transfected group

Our previous study showed that cortactin is involved in sheer stress-induced mucin secretion by regulating F-actin polarization [10]. In this study, neutrophil elastase induced MUC5AC secretion and production, with phosphorylation of cortactin and arrangement of F-actin. Subsequently, we transfected the cells with cortactin (CTTN) siRNA, which resulted in a reduction of MUC5AC secretion and decreased localization of F-actin at the cell membrane. SiRNA-mediated knockdown of both MARCKS and CTTN resulted in stronger attenuation of MUC5AC secretion and F-actin arrangement than that of CTTN siRNA-transfected cells or MARCKS siRNA-transfected cells alone, indicating that both MARCKS and cortactin could promote mucin secretion by stabilizing F-actin polymerization. We also found that cortactin phosphorylation can be restrained by MARCKS siRNA, which is consistent with a previous report that MARCKS could influence the activation and translocation of cortactin [41].

Activated CDC42 kinase 1 (ACK1/TNK2) was initially identified as a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that specifically binds to the GTP-bound form of Cdc42; it shuttles between the cytosol and the nucleus to rapidly transduce extracellular signals from tyrosine kinases to intracellular effectors. Recent data have shown that it is involved in the development of multiple malignancies [42], inflammation and autoimmune diseases [43]. Activated Cdc42 leads to actin polymerization into filopodia, and the downstream effectors of Cdc42 and ACK are also activated. Here, we further investigated whether MARCKS could also regulate ACK1. We found that NE induced ACK1 (Y284) activation in cells. MARCKS siRNA but not CTTN siRNA inhibited the expression of p-ACK1, whereas ACK1 siRNA inhibited p-cortactin expression. Co-immunoprecipitation showed that cortactin and ACK1 combined, suggesting that MARCKS may regulate ACK1, and ACK1 binds to and then activates cortactin to promote the polarization of F-actin.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, we exclusively used NE as a mucus inducer in this study, so further research is necessary to ascertain whether the mucus secretion mechanism we investigated is specific to NE stimulation or more general. Secondly, given that we only used a cell line of undifferentiated epithelium in a basal state, whether this mechanism would extend to differentiated epithelium, specialized secretory cells or the entire airway needs further investigation. Thirdly, it is worth exploring whether this mechanism exclusively targets MUC5AC secretion or also influences other mucins, such as MUC5B.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study described the interaction of cortactin and MARCKS in airway epithelial cells. Both molecules are membrane-tracking proteins that can modulate cytoskeletal signaling and promote mucin secretion under NE stimulation. ACK1 may serve as an intermediator for this interaction. The overall effects of cortactin and MARCKS in airway inflammatory diseases still need further elucidation. Future research should investigate whether gene polymorphisms of MARCKS and cortactin influence F-actin arrangement, regulate mucin secretion, or affect the production of inflammatory cytokines.