Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) is a bacterium with specific characteristics having a wide range of clinical manifestations, in which respiratory infections are the most common presentation [1]. As a small cell wall-lacking pathogen, MP is a common reason for bronchitis and pneumonia in patients [2]. Infections caused by MP can progress to serious respiratory complications and need intensive care treatment [3]. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is associated with high morbidity and represents a growing global burden [4]. Notably, MP is sensitive to macrolide antibiotics [5].

Azithromycin is in the macrolide class of antimicrobials. This antimicrobial drug is used in the treatment and management of bacterial infections, such as community-acquired pneumonia [6]. Additionally, azithromycin is demonstrated to possess a large number of benefits because of its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects [7]. As a macrolide antibiotic, azithromycin has the ability to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis and reduce biofilm formation. In addition, azithromycin is indicated for respiratory bacterial infections, and exerts an immunomodulatory impact on chronic inflammatory disorders, with a very good safety record [8]. Azithromycin is also reported to possess antioxidant capacity and can attenuate oxidative stress injury induced by cigarette smoke extract [9]. Azithromycin possesses anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties and can mitigate radiation-induced acute lung injury [10]. Inflammatory responses and oxidative stress are reported to be linked to the occurrence of lung injury in a variety of disorders, and azithromycin is demonstrated to effectively prevent injury in lung tissues, and ameliorate the contents of pro-inflammatory markers and oxidative stress indicators [11]. Azithromycin is also regarded as the preferred agent in MP treatment [12]. The combination of azithromycin and ulinastatin is able to quickly improve clinical symptoms, control the development of those with severe mycoplasma pneumonia, and markedly improve inflammatory infection markers and blood oxygen levels [13]. The combination treatment of azithromycin and methylprednisolone has the capability to suppress MP infection-induced inflammation and loss of cell viability [14]. Furthermore, the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2/antioxidant response element (Nrf2/ARE) pathway is an intrinsic mechanism for defending against oxidative stress. Nrf2 is a transcription factor that can induce the expression of a large number of cellular protective and detoxifying genes. The protective role of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases has been highlighted, as it can reduce oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [15]. On the basis of the above reports, we initiated our research and aimed to uncover the underlying mechanism of action of azithromycin on lung oxidative injury and immune function in MP-infected mice based on the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway.

Material and methods

Experimental animals

Thirty specific pathogen free (SPF)-grade BALB/c juvenile mice, half male and half female, aged 4 weeks old, with a body weight of 20 ±2 g, were provided by Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China) (Laboratory Animal Production License: SYXK [Beijing] 2022-0052). The feeding conditions were as follows: room temperature of 25 ±2°C, humidity of 50 ±10%, and 12 h/12 h light and dark cycle. The mice freely accessed water and food during the experiment.

Grouping, modelling, and drug delivery methods

After one week of adaptive feeding, the mice were randomly separated into the control group, MP group, azithromycin (AZI) group, MP + AZI group, MP + DMSO group, and MP + sulforaphane (Nrf2 activator, SFN) group, with 10 mice in each group. Except for the control and AZI groups, the mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and inoculated intranasally with 100 μL (1 × 107 CCU/ml) of MP suspension (standard strain purchased from Shanghai Baitai Medical Technology Co., Ltd.) for 3 days consecutively. The head of the mice was tilted backwards at 45ofor about 1 min after the inoculation. Mice in the control group and AZI group were inoculated by nose-drip with 100 μl of normal saline. The success of the modelling was initially determined when the mice were observed to have poor mental status, decreased dietary amount, and increased nasal secretion and nose scratching. One day after successful modelling, mice in the MP + AZI and AZI groups were gavaged with azithromycin (32 mg/kg/day, manufactured by Pfizer Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.), while mice in the MP + SFN and MP + DMSO groups were injected intraperitoneally with sulforaphane (5 mg/kg/day) or an equivalent volume of DMSO for seven consecutive days. The control group and MP group received an equal volume of saline by gavage [16-19].

After the treatment was completed, blood samples were collected by enucleation. The mice were grasped to protrude their eyes, and the protruding eyes were removed with tweezers. The orbit was immediately turned downward to allow the blood to drip into a centrifuge tube. A total of 1 ml of blood was collected from each mouse and stored at –20°C for future use. After blood collection, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and their body weight was measured. The chest skin was incised; the trachea was separated; the right lung was ligated; a disposable infusion tube was inserted; 2.5 ml of saline was injected; the alveoli were lavaged, and the alveolar lavage fluid was collected. The whole lung tissues of mice were extracted and weighed, and then the lung index was calculated: lung index = (lung mass/body mass) × 100%. The lower lobe of the left lung was taken, weighed individually and then placed in a thermostat at 80°C for 48 h. After that, it was weighed again and the dry/wet weight ratio was calculated. A portion of the remaining lung tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, while another portion was stored at –80°C for the detection of oxidative stress indicators, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), and Western blotting (WB).

ELISA for alveolar lavage fluid inflammatory factors

A microplate reader was employed to measure optical density (OD) at 450 nm. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-10, and IL-6 contents in alveolar lavage fluid were calculated. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were provided by Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China) [20].

Table 1

Primer sequences for RT-qPCR

ELISA for serum interferon γ and immunoglobulin G levels

To obtain serum, the collected blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 r/min, and then serum interferon γ (IFN-γ) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels were assessed. The IFN-γ assay kit was obtained from Shanghai Kemin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the IgG assay kit was obtained from Shanghai Future Industry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Flow cytometry for peripheral blood T-lymphocyte subsets

A total of 100 μl of anti-coagulated blood was collected. After centrifugation, the supernatant was aspirated, supplemented with 2 ml of erythrocyte lysate, mixed, and cultivated at ambient temperature for 5 min. Next, the mixture was centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 5 min, and the supernatants were discarded. The cells were rinsed with 1 ml of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) twice and re-suspended with PBS. A total of 10 μl of CD3-PE, CD4-FITC, and CD8-647 fluorescent antibody (Becton Dickinson, USA) was supplemented, mixed, and incubated at ambient temperature while avoiding light for 30 min. CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ quantities as well as their percentages and CD4+/CD8+ ratio were determined using flow cytometry (Beckman, USA) [21].

Colorimetric detection of oxidative stress indicators in lung tissues

The lung tissue homogenates were prepared in an ice-water bath at 4°C, and the supernatants were taken after centrifugation at 1000 × g for 20 min. Then 20 μl of the supernatant was taken, fully mixed with the working solution, and cultured at 37°C for 25 min. The OD value at 450 nm was assessed and malondialdehyde (MDA) contents and superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH) activity were calculated. All kits were provided by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

HE staining for pathological changes in lung tissues

At the end of treatment, the lung tissues were taken, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, rinsed in distilled water, dehydrated in gradient ethanol, permeabilized in xylene, paraffin-embedded, and sliced into 4-μm-thick sections. Tissue slices were routinely dewaxed and rehydrated, stained by implementing hematoxylin and eosin, sealed with neutral gum, and then observed under a light microscope for histopathological changes in the lungs. The severity of lung injury was tested by implementing a semi-quantitative histological score by a double-blind method. Next, the histopathological score was assessed on the basis of bronchial or peribronchial infiltration, perivascular and leukocyte infiltration, and bronchial or bronchial exudate, each assigned a level of 0 to 3 (0 = no injury; 1 = mild injury; 2 = moderate injury; 3 = serious injury). These calculated scores were applied for statistical analysis [20, 22].

RT-qPCR for Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 mRNA expression levels in lung tissues

Total RNA was isolated from lung tissues using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA). Then, to quantify mRNA levels, real-time PCR was conducted on an ABI 7300 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo). The 2-ΔΔCt method was applied to acquire the relative expression levels of target genes, and β-actin was considered as an internal reference. All the primer sequences are displayed in Table 1 [18].

WB for Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 protein expression levels in lung tissues

A total of 20 mg of mouse lung tissues were taken, lysed by supplementing radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis solution, homogenized in an automatic homogenizer, and placed on ice for 30 min to be fully lysed. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method was employed to determine the protein concentration. The same amount of protein was electrophoresed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, and blocked by implementing 5% skimmed milk powder at ambient temperature for 2 h. Then, the membrane was supplemented with Nrf2 (1 : 1000), HO-1 (1 : 2000), NQO1 (1 : 1000), and β-actin (1 : 5000) primary antibodies (all antibodies were purchased from Abcam), cultivated overnight at 4°C, rinsed well with Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST), supplemented with HRP-labelled secondary antibody (1:1000) added dropwise, cultured at ambient temperature for 2 h, and fully rinsed with TBST. The enhancement solution in enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent was mixed with stabilized peroxidase solution at a ratio of 1 : 1, and the working solution was supplemented dropwise onto a PVDF membrane, which was then developed on a gel imaging system. The protein expression levels, defined as the ratio of the absorbance of the target band to the absorbance of the internal reference band of β-actin, were analyzed using Bio-Rad Image Lab software [23].

Statistical analyzis

SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM, USA) was applied for statistical analysis of data. Measurement data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and comparisons among multiple groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s post-hoc test. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test was applied for comparisons of histopathological scores among groups, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Images were drawn using GraphPad Prism 9.4.0 software.

Results

Lung index, dry/wet weight ratio and alveolar lavage fluid inflammatory factor levels

Mice in the MP group showed a higher lung index, lower lung dry/wet weight ratio, higher levels of alveolar lavage fluid inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and a lower IL-10 level than in the control group (all p < 0.05). No significant differences in the aforementioned indicators between the AZI group and control group were observed (p > 0.05). Compared to the MP and MP + DMSO groups, mice in the MP + AZI and MP + SFN groups exhibited a lower lung index, higher lung dry/wet weight ratio, lower contents of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and a higher IL-10 level (all p < 0.05, Fig. 1A-F).

Immune function indicator levels

Mice in the MP group expressed higher serum levels of IFN-γ and IgG, and peripheral blood CD8+ levels, and lower CD3+ levels, CD4+ levels and CD4+/CD8+ ratio than in the control group (all p < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference in the levels of immune function indicators between the control group and AZI group of mice (p > 0.05). After azithromycin and SFN treatment, reduced serum IFN-γ and IgG, and peripheral blood CD8+ levels, and elevated CD3+ levels, CD4+ contents, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio were observed (all p < 0.05, Fig. 2A-F).

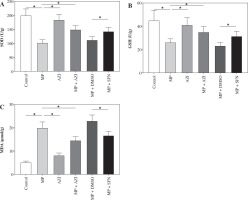

Oxidative stress indicator levels in mouse lung tissues

Mice in the MP group showed lower SOD and GSH activity and higher MDA contents versus the control group (p < 0.05). No significant changes in SOD, GSH activity, and MDA content in the mice in the AZI group were found (p > 0.05). Compared to the MP and MP + DMSO groups, mice in the MP + AZI and MP + SFN groups displayed up-regulated SOD and GSH activity and diminished MDA contents (p < 0.05, Fig. 3).

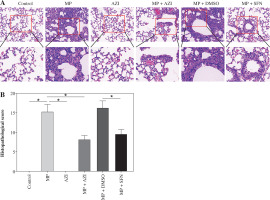

Mouse lung histopathological changes and scores

HE staining was implemented to observe lung histopathological changes in each group of mice and to determine pathological scores. The results indicated that the lung tissues of mice in the control and AZI groups had intact alveolar structure, thin alveolar wall, no inflammatory cell infiltration, and intact and clear fine bronchial structure. Mice in the MP group displayed damaged lung tissues, thickened alveolar walls, large area of inflammatory cell infiltration, and loss of some alveolar luminal structures, but elevated pathological scores; after intervention with azithromycin and SFN, the mice had less lung tissue injury, better alveolar structural integrity, alleviated inflammatory cell infiltration, and lower pathological scores than the MP and MP + DMSO groups (all p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A-B).

Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 expression levels in mouse lung tissues

To ascertain whether azithromycin treated MP infection through modulation of the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway, RT-qPCR and WB were carried out to assess Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 expression levels in mouse lung tissues. The findings revealed that Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 mRNA and protein levels in the lung tissue of mice in the MP group were lower than those of the control group (p <0.05), while there were no significant changes in the AZI group (p > 0.05). In comparison to the MP group and the MP + DMSO group, Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 mRNA and protein levels in the lung tissues of mice in the MP + AZI group and the MP + SFN group were elevated (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5A-C).

Discussion

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an obligate pathogenic bacterium without a cell wall, which can lead to severe upper respiratory tract symptoms [24] and result in pneumonia in animals and humans [25]. Our study probed the underlying mechanism of action of azithromycin on lung oxidative injury and immune function in MP-infected mice based on the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway.

Fig. 1

Comparison of lung index, dry/wet weight ratio and alveolar lavage fluid inflammatory factor levels. A) Comparison of lung index in each group of mice. B) Comparison of lung dry/wet weight ratio in each group of mice. C-F) Comparison of alveolar lavage fluid inflammatory factor levels in each group of mice. ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05

Fig. 2

Comparison of serum immune function indicator levels. A) Comparison of serum IFN-γ levels in each group of mice. B) Comparison of serum IgG levels in each group of mice. C-F) Comparison of peripheral blood T lymphocyte subsets in each group of mice. ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s posthoc test. *p < 0.05

Fig. 3

Comparison of the levels of oxidative stress indicators. A) Comparison of MDA contents in lung tissues in each group of mice. B) Comparison of SOD activity in lung tissues in each group of mice. C) Comparison of GSH activity in lung tissues in each group of mice. ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05

Fig. 4

Comparison of histopathological changes and pathological scores. A) Representative images of pathological changes in lung tissues in each group of mice observed under HE staining. B) Comparison of pathological scores of lung tissues in each group of mice. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for comparisons between multiple groups. ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05

Fig. 5

Comparison of Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 expression levels. A) RT-qPCR detection of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO1 mRNA expression levels in the lung tissues of mice in each group. B, C) WB detection of Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 protein expression levels in the lung tissues of mice in each group. ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05

In our study, we found that, compared to the control group, mice infected with MP exhibited an elevated lung index and a decreased lung dry/wet weight ratio, indicating exacerbation of lung edema and inflammation. Simultaneously, elevated levels of inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were observed in alveolar lavage fluid, accompanied by a reduction in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, further confirming the lung inflammatory response induced by MP infection. These changes suggest that MP infection triggers a robust inflammatory reaction. However, following intervention with azithromycin and SFN, the mice showed a decreased lung index, an increased lung dry/wet weight ratio, reduced levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in alveolar lavage fluid, and elevated IL-10 levels. This indicates that azithromycin can reduce the inflammatory levels in MP-infected mice. As previously reported, azithromycin is a synthetic macrolide antibiotic and is effective in treating bacterial and mycobacterial infections with a range of anti-inflammatory properties [26]. Moreover, azithromycin has the ability to suppress cigarette smoke-induced expression of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [27]. A previous study also demonstrated that azithromycin can effectively boost IL-10 levels in cisplatin-administered rats [11].

A study demonstrated that one of the potent anti-inflammatory mechanisms of azithromycin is through the suppression of CD4+ helper T cell effector function. Moreover, azithromycin can repress production of the inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and IL-4 [28]. This study revealed that in contrast with the control group, MP infection in mice led to elevated levels of serum IFN-γ and IgG, as well as peripheral blood CD8+, while the levels of CD3+, CD4+, and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio diminished, implying suppression of the mice’s immune function. Nevertheless, after treatment with azithromycin and SFN, these immune function indicators improved: the levels of serum IFN-γ, IgG, and peripheral blood CD8+ decreased, while the levels of CD3+ and CD4+ and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio increased. This suggests that azithromycin can enhance the immune function of MP-infected mice. In addition, it has been reported that azithromycin treatment can reduce the levels of MDA in mice [10]. Liu Xiu-Xiu et al. confirmed that exosomal microRNA-222-3p downregulates the activity of SOD2 but promotes the activity of nuclear NF-κB and the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in human alveolar basal epithelial cells, ultimately leading to a state of oxidative stress [29]. GSH is an important antioxidant that neutralizes reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species, while maintaining redox balance and detoxifying xenobiotics [30]. The results of this study showed that MP-infected mice had decreased SOD and GSH activity and increased MDA content. In comparison with the MP group and the MP + DMSO group, the MP + AZI group and MP + SFN group showed upregulated SOD and GSH activity and reduced MDA content. This means that azithromycin can improve the oxidative stress levels in MP- infected mice. Furthermore, we also observed that after azithromycin and SFN intervention, the mice exhibited less lung tissue damage, better alveolar structural integrity, less inflammatory infiltration, and lower pathological scores compared to the MP group and MP + DMSO group. This indicates that azithromycin can improve the degree of lung tissue damage and reduce the pathological score in MP-infected mice.

Data suggest azithromycin possessed apparent reversion effects on cigarette smoke-induced Nrf2 repression [31]. Azithromycin can elevate Nrf2 and HO-1 in the lungs of cisplatin-treated rats, and the protective effects of azithromycin are associated with up-regulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway [11]. This study demonstrated that after azithromycin and SFN intervention, the levels of Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 mRNA and protein were increased in the lung tissue of MP-infected mice. These molecules are key components of the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway, which can induce the expression of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes, thereby enhancing the cellular antioxidant capacity. Therefore, azithromycin can protect against MP-induced lung injury by activating the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway.

In summary, this research demonstrated that azithromycin can ameliorate MP infection-induced lung injury and oxidative stress and strengthen immune function in mice, which might be achieved through the activation of the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. The present research offers a novel approach for developing an effective and applicable treatment for lung injury and oxidative stress induced by MP infection. However, it is subject to certain limitations, including a relatively small sample size and inadequate exploration of the mechanisms underlying the influence of the Nrf2/ARE axis on lung oxidative injury and immune function in MP-infected mice. Further exploration is needed for further corroboration of our findings.