Introduction

According to the latest World Cancer Report, breast cancer has become the leading malignant tumor globally, with an incidence rate much higher than that of lung cancer, posing a significant threat to women’s physical and mental health [1, 2]. In the United States, approximately 12.8% of women are diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetime [3]. Breast cancer exhibits diversity in histological type, natural history, clinical behavior, and response to treatment. Current treatments for breast cancer include a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, endocrine therapy, and radiotherapy [4]. However, recurrence or metastasis occurs in about 30% of patients, and chemotherapeutic drugs often have limitations, such as toxic side effects and uncontrollable drug resistance, reducing their clinical efficacy [5]. Thus, there is an urgent need to explore more effective therapeutic targets for breast cancer treatment.

Pyroptosis, also known as inflammatory cell death, is a recently identified type of programmed cell death. It involves regulated cell demise mediated by pore formation in the cell’s plasma membrane by gasdermin proteins, leading to cell swelling, membrane rupture, and the release of cellular components that trigger an inflammatory reaction [6-8]. Research into the connection between cellular pyroptosis and human diseases has gained momentum in recent years. Li et al. revealed a molecular mechanism by which isoliquiritin ameliorates depression by inhibiting pyroptosis [9]. Cellular pyroptosis has also been linked to GAS5 amelioration of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [10]. Additionally, miRNA-214 was shown to inhibit cervical cancer progression by targeting NLRP3, promoting cervical cancer cell death [11], and nobiletin was found to promote breast cancer cell pyroptosis via the miR-200b/JAZF1 axis [12]. Therefore, pyroptosis represents a potential therapeutic mechanism for various human diseases, including cancer.

Interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 are pyroptosis-associated inflammatory factors [13]. These cytokines are primarily activated and released during pyroptosis, which is a form of inflammatory cell death triggered by the activation of inflammasomes. When inflammasomes (such as NLRP3) are activated, they lead to the activation of caspase-1. Caspase-1, in turn, cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms (IL-1β and IL-18), which are then released from the cells, contributing to inflammatory responses [14].

Exportin-T (XPOT) is a transporter protein belonging to the Ran-GTPase family of nuclear transporter proteins (karyopherin family) [15, 16]. It is involved in the progression of several human diseases. For instance, XPOT is considered a potential therapeutic and diagnostic target for neuroblastoma [17]. Lin et al. found that overexpression of XPOT promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion [18], and Suzuki et al. reported that increased XPOT expression is associated with cell proliferation in human promyelocytic leukemia [19]. Bioinformatics analyses by Mehmood et al. identified XPOT as a molecule linked to poor prognosis in breast cancer patients [20]. However, the specific role of XPOT in breast cancer progression and its molecular mechanisms remain unknown.

In our study, we aimed to investigate whether XPOT inhibited breast cancer progression by modulating pyroptosis.

Material and methods

Clinical specimens

All human breast cancer samples and adjacent samples were collected between January 2022 and January 2023 after obtaining approval from the ethics committee (approval No. ZSLL-KY-2023-062-01) at our hospital and written consent from all patients. All patients were diagnosed with breast cancer and had not received radiotherapy or chemotherapy prior to surgery.

GEPIA database analysis

We analyzed XPOT expression in breast cancer samples using the GEPIA database. By typing “XPOT” in the search box, selecting “Breast Cancer” in the Cancer Type option, choosing “Boxplot Graphics” in the Picture Type option, and clicking “OK”, we obtained the results regarding XPOT expression levels in breast cancer.

Cell culture

Normal mammary epithelial cells (MCF10A) and various breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, BT-549, MCF-7, and HCC1937) were obtained from Meisen. Breast cancer cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Biosharp, BL301A, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Beyotime, C0227, China) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biosharp, BL505A, China). Normal mammary epithelial cells were cultured in mammary epithelial cell growth medium (Lonza, CC-3150, Switzerland). All cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cell transfection and treatment

To knock down XPOT expression, we constructed small interfering RNAs specifically targeting XPOT (si-XPOT: 5′-CGAAGUUAUAGCAAAUCAA-3′) and a scramble sequence (si-NC: 5′-CACGATAAGACTTTAATGTATTT-3′). si-XPOT was transfected into cells using transfection reagents (Beyotime, C0526, China) when cells reached approximately 60% confluence. Cells were collected for subsequent experiments 24 hours after transfection. To inhibit pyroptosis, cells were treated with the pyroptosis inhibitor azalamellarin N (MCE, HY-162150, USA) for 24 hours before sample collection.

CCK-8 assay for cell viability

Transfected or treated cells were inoculated into 96-well plates, with around 2500 cells per well. After stabilizing cell attachment, the medium was discarded, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; MCE, HY-K3005, USA) twice, and 10 μl of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay solution (Vazyme, A311-01, China) was added to each well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 20-30 minutes, protected from light, and then detected at 450 nm.

TUNEL assay

Cell death was assessed using the TUNEL fluorescence assay kit (CST, 25879S, USA). Cells were transfected or treated with azalamellarin N, washed with PBS, fixed, and permeabilized. TdT-labeled working solution was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Nuclei were stained with DAPI working solution (Beyotime, C1005, China), washed with PBS twice, and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, CKX53, Japan).

Cell scratching assay

Cells were grown to 100% confluence, and a scratch was made using a sterile pipette tip. The medium was discarded, cells were washed with PBS twice, and serum-free medium was added. After 24 hours, cell photographs were taken for observation using an inverted microscope (Olympus, IX73, Japan) equipped with a 10× objective. The scratch area was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA) to analyze the scratch width at different time points.

Transwell assay

Cells were pre-treated with transfection or pyroptosis inhibitor before the Transwell experiments. For migration assays, cells were resuspended in serum-free medium and inoculated in the upper layer of Transwell chambers, with medium containing 20% FBS in the lower layer. For invasion assays, the upper layer of Transwell chambers was coated with matrix gel (Yeasen, 40187ES08, China), and medium with 20% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, washed with PBS, fixed, stained with crystal violet solution (Beyotime, C0121, China), and observed under a microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor and adjacent samples from clinical patients were fixed, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned into 5 μm sections. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and antigenically repaired, then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin solution (Yeasen, 36101ES25, China). Sections were incubated with XPOT antibody (Affinity, DF13834; 1 : 200 dilution, China) for 4-6 hours, washed with PBS, re-incubated with a secondary antibody containing horseradish peroxidase (Affinity, S0001, China), and developed with DAB (Yeasen, 36201ES03, China). Images of the stained sections were captured using a microscope (Nikon, Eclipse E200, Japan) equipped with a 20× objective. Quantitative image analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

Western blotting

Cells were treated with RIPA lysate (Yeasen, 20101ES60, China) containing 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; MCE, HY-B0496, USA) on ice. Lysates were collected and centrifuged to obtain protein samples. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA quantification kit (Vazyme, E112-01, China), boiled at 100°C for 10 minutes with SDS loading buffer (Biosharp, BL502B, China), and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Yeasen, 36124ES10, China) that was then blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder (Millipore, 70166, USA), and incubated with primary antibodies against GSDMD (Affinity, DF12275, China), NLRP3 (Affinity, DF15549, China), ASC (Affinity, DF6304, China) and cleaved-caspase1 (Affinity, AF4005, China) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed with PBST (Biosharp, BL314B, China), incubated with secondary antibodies (Affinity, S0001, China), washed again, and visualized using ECL chemiluminescent solution (Biosharp, BL523A, China).

Results

Elevated XPOT expression in breast cancer

To investigate XPOT expression levels in breast cancer, we analyzed data from the GEPIA database, which indicated elevated XPOT expression in breast cancer tissues (Fig. 1A). Immunohistochemistry of clinical samples confirmed higher XPOT expression in breast cancer tissues compared to adjacent samples (Fig. 1B). XPOT expression was assessed in normal breast epithelial cells and various breast cancer cell lines using Western blotting. XPOT expression was higher in breast cancer cell lines, with the highest expression in MCF-7 cells, which were selected for subsequent experiments (Fig. 1C).

Inhibition of XPOT expression suppresses MCF-7 cell viability and metastasis

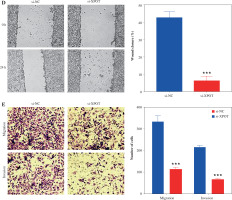

To clarify the effect of XPOT on breast cancer cells, we constructed XPOT small interfering RNA and transfected it into MCF-7 cells. Western blotting showed that si-XPOT significantly inhibited XPOT expression in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2A). CCK-8 assay results showed that cell viability was significantly suppressed in the si-XPOT group compared to the si-NC group (Fig. 2B). TUNEL staining indicated an increased proportion of TUNEL-positive cells in the si-XPOT group (Fig. 2C). Scratch assay results suggested reduced metastatic motility after XPOT expression interference (Fig. 2D). Transwell assays showed consistent results, with reduced migration and invasion in the si-XPOT group (Fig. 2E). These results indicated that inhibiting XPOT expression suppresses cell viability, promotes cell death, and inhibits cell metastasis.

Inhibition of XPOT expression induces pyroptosis in MCF-7 cells

To determine whether XPOT induces pyroptosis in MCF-7 cells, we examined pyroptosis markers. ELISA results showed significantly higher levels of IL-18 and IL-1β in the si-XPOT group compared to the si-NC group (Fig. 3A). Western blotting results indicated elevated expression of the N-terminal shear body of GSDMD after XPOT inhibition (Fig. 3B). Western blotting results also showed increased expression of inflammasome proteins NLRP3, ASC, and cleaved-caspase 1 in the si-XPOT group (Fig. 3C). These results confirmed that XPOT inhibition promotes pyroptosis in MCF-7 cells.

XPOT affects MCF-7 viability and metastasis by regulating pyroptosis

To verify whether XPOT affects breast cancer cell biological processes by regulating pyroptosis, we treated cells with the pyroptosis inhibitor azalamellarin N. CCK-8 results showed that azalamellarin N reversed the suppression of cell viability induced by si-XPOT (Fig. 4A). TUNEL assay results indicated that azalamellarin N reversed the increase in TUNEL-positive cells caused by si-XPOT (Fig. 4B). Scratch assay results showed a higher wound healing rate in the si-XPOT + azalamellarin N group compared to the si-XPOT group (Fig. 4C), and Transwell assay results showed significantly increased migration and invasion in the si-XPOT + azalamellarin N group (Fig. 4D). ELISA results indicated decreased IL-18 and IL-1β secretion after azalamellarin N treatment compared to the si-XPOT group (Fig. 4E). Western blotting results showed decreased N-GSDMD and lower expression of NLRP3, ASC, and cleaved-caspase1 in the si-XPOT + azalamellarin N group compared to the si-XPOT group (Fig. 4F, G). These results suggest that azalamellarin N inhibits pyroptosis induced by si-XPOT.

Fig. 1

Expression of XPOT in breast cancer. A) Database analyses of XPOT expression. B) XPOT expression in tissues was detected by immunohistochemistry (scale bar: 500 μm). C) XPOT expression in normal cells and cancer cell lines. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with MCF10A cells. Three replicate experiments were performed. Data are exhibited as mean ± standard deviation

Fig. 2

Effects of XPOT on MCF-7 cells. A) Western blotting for transfection efficiency. B) CCK-8 assay for cell viability. C) Levels of programmed cell death detected by TUNEL assay. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with si-NC group. D) Scratch assay of cell metastatic capacity. E) Transwell assay for cell migration and invasion ability. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with si-NC group. Three replicate experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

Fig. 3

Effect of XPOT on pyroptosis of MCF-7. A) Levels of IL-1β and IL-18. B) Protein level of GSDMD. C) Inflammasome complex protein levels determined by Western blotting. ***p < 0.001, compared with si-NC group. Three replicate experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

Fig. 4

XPOT affected breast cancer progression by regulating breast cancer cell pyroptosis. A) Cell viability of MCF-7. B) Detection of cell death by TUNEL assay. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with si-XPOT group. Three replicate experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation C) Cell motility was measured by scratch assay. D) Migration and invasion of MCF-7 were determined by Transwell assay. E) Levels of IL-1β and IL-18. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with si-XPOT group. Three replicate experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation F) Level of GSDMD. G) Protein levels of NLRP3, ASC and cleaved-caspase 1. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with si-XPOT group. Three replicate experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

Discussion

Globally, breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor in women, accounting for 23% of all cancer cases [21]. Its incidence is rising, and despite advancements in diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities, breast cancer remains a leading cause of female deaths [22]. In 2018, over 2 million cases of breast cancer were reported according to the Global Cancer Observatory [23]. Significant toxicity and emerging resistance to anticancer drugs make cancer treatment challenging [24]. Therefore, new treatment strategies are essential to reduce the annual cancer death rate [25-27].

Cell death is a physiological regulator of cell proliferation, stress response, and homeostasis, and a tumor suppressor mechanism [28]. Tumors employ various strategies to circumvent or limit cell death pathways, acting as a protective mechanism [29]. In cancer treatment, cell death is beneficial, with several known types, including apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis [30]. In recent years, the molecular mechanisms of tumor cell pyroptosis and the factors inducing pyroptosis have been extensively studied [31]. Lei et al. demonstrated that azurocidin 1 induces breast cancer cell pyroptosis and inhibits cancer cell proliferation [32]. Additionally, hexokinase 2 was shown to induce GSDME-dependent pyroptosis, reversing the immunosuppressive microenvironment and inhibiting breast cancer progression [33]. Chen et al. also highlighted the potential of targeting pyroptosis in breast cancer, showing that pyroptosis inducers significantly enhanced immune cell infiltration into tumor tissues, thereby transforming “cold” tumors into “hot” ones. This improved responses to immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors [34]. Our study explored the potential of inducing pyroptosis as a novel therapeutic target for breast cancer. The results indicate that inducing pyroptosis in breast cancer cells inhibits their activity, migration, and invasion.

XPOT, a transporter protein, has been associated with various cancer processes in previous studies. It has been reported as a diagnostic and therapeutic target for breast cancer [35] and hepatocellular carcinoma [36]. Pan et al. also identified XPOT as a novel prognostic predictor and therapeutic target in neuroblastoma, highlighting its broader implications across various malignancies. Inhibition of XPOT may disrupt cancer cell growth by blocking the nuclear export of tRNAs, leading to a breakdown in protein synthesis machinery and impaired cancer cell proliferation [17]. Notably, Verma et al. demonstrated that 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, a derivative of vitamin D, can regulate breast cancer cell behavior both in vitro and in vivo by modulating XPOT activity. These compounds may act as a potential adjunct therapy to target XPOT and disrupt cancer progression [37]. Our findings suggest that knockdown of XPOT expression in MCF-7 cells suppresses cell proliferation and metastasis. Treatment with the pyroptosis inhibitor azalamellarin N reveals that the inhibitory effects of XPOT siRNA on MCF-7 cells are mediated through promoting pyroptosis. Probably, azalamellarin N inhibits pyroptosis by acting on upstream molecules involved in the NLRP3 inflammasome activation pathway, specifically targeting signals that lead to inflammasome formation rather than NLRP3 itself. This small molecule affects critical cellular processes such as ion flux and the production of reactive oxygen species, both of which are necessary for NLRP3 inflammasome assembly. By disrupting these early signals, azalamellarin N prevents activation of caspase-1 and subsequent cleavage of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, thereby suppressing pyroptosis [38-40].

Nevertheless, this study is limited. The genetic characteristics of the cell lines and the possible influences on the results are not considered. Additionally, tumor tissues are heterogeneous, and small biopsy samples may not represent the entire tumor’s protein expression profile. These limitations may cause bias that needs to be solved in future studies.