Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequent cancer globally and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths, according to a review of global cancer statistics for 2022. CRC accounts for 9.6% of cancer cases worldwide [1]. According to estimates, there will be a 73.4% rise in CRC-related mortality between 2020 and 2040 [2]. The complicated pathogenic processes of CRC are intimately linked to the disease’s escalating incidence and fatality rates [3]. The tumor microenvironment (TME), which is made up of immune cells (macrophages, T cells, etc.), stromal cells (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, etc.), and extracellular matrix components (fibronectin, laminin, etc.), has an important role in the processes that are most important for the growth of tumors [4, 5]. Macrophages are essential elements of the TME. They are diverse and plastic [6] and interact extensively with cancer cells to influence the growth of tumors [7, 8]. Therefore, it is essential to understand the mechanisms behind cancer progression and worsening to identify biomarkers in CRC and investigate the connection between tumor cells and macrophages.

Remarkably, macrophages polarize in response to TME stimuli, mainly becoming classically activated (M1) or alternatively activated (M2) macrophages [9]. Helper T cell (Th) 1 immune responses are known to be enhanced by M1 macrophages, but anti-inflammatory Th2 immune responses are enhanced by M2 macrophages [10, 11]. Macrophages primarily polarize toward the M2 phenotype in the TME, where they can promote tumor development, sustain immune suppression, and regulate angiogenesis, among other malignant consequences [12]. For example, via activating the c-myc/PKM2 pathway, NFATc1 causes M2 polarization in macrophages to enhance cervical cancer growth [13]. Furthermore, research shows that Oct4 in lung cancer increases M-CSF production, which causes macrophage M2 polarization and ultimately tumor development and metastasis [14]. Tumor cells in the TME polarize macrophage M2 via a variety of ways, impacting the course and metastasis of cancer and providing a major area of study for the field. Nevertheless, how tumor cells in CRC drive their malignant development by stimulating macrophage M2 polarization is not fully known and requires further research.

Basement membrane laminin is a glycoprotein that is extensively distributed and plays a crucial role in the extracellular matrix. It plays important roles in processes including cancer, metastasis, and tissue repair by interacting with cell surface receptors to enhance cell adhesion, migration, and directional movement [15, 16]. Laminin subunit α1 (LAMA1) is a member of the laminin family [17]. Elevated LAMA1 levels are frequently linked to tumor growth and a bad prognosis in some malignancies. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0000277, for instance, sequesters miR-4766-5p to upregulate LAMA1 expression and accelerate the course of esophageal cancer [18]. By binding to LM-111, LAMA1 promotes VEGFA production through the integrin α2β1-CXCR4 pathway, causing colon cancer cells to proliferate and undergo angiogenesis [19]. In conclusion, LAMA1 contributes significantly to the onset and progression of cancer; nevertheless, the significance of this protein in CRC is comparatively underreported, requiring more studies to clarify its roles in CRC and investigate its potential as a target for treatment.

We found that CRC had considerably higher levels of LAMA1 expression in our investigation. Furthermore, LAMA1 promoted the malignant development of CRC by activating the EGFR/AKT/CREB pathway, which in turn caused M2 polarization of macrophages. Overall, our study explored how LAMA1 functional modulation affected macrophage polarization in the TME as well as the incidence and progression of CRC. These groundbreaking discoveries provide fresh insight into the potential therapeutic target for LAMA1 and the pivotal roles played by macrophages and LAMA1 in the development of CRC.

Material and methods

Cell culture

BeNa Culture Collection (BNCC, China) provided the human normal colonic epithelial cells NCM-460 (BNCC339288) and the two CRC cell lines RKO (Rhesus monkey kidney cells, Ovarian carcinoma) (BNCC100173) and LoVo (Lymphoma of the Ovarian origin, Variant of the Ovarian carcinoma) (BNCC338601). The Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences provided the human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 (TCHu 57). 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added to DMEM-H complete medium (BNCC338068, China) for the cultures of NCM-460 and RKO, and 10% FBS was added to F-12K complete medium (BNCC338550, China) for the cultures of LoVo. 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol (CAS No.: 60-24-2, Merck, Germany) [20, 21] and 10% FBS were included in the RPMI-1640 complete media (BNCC338360, China) used to sustain THP-1 cells. Every cell was cultivated at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (PB180120, Procell, China) was added as a supplement.

Cell transfection

As directed by the manufacturer, cells were transfected with oe-NC, oe-LAMA1, si-NC, and si-EGFR, which were produced by RiboBio (China) and transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen, USA). RKO cells were transfected with oe-NC and oe-LAMA1, while THP-1 cells were transfected with si-NC and si-EGFR.

Macrophage M0 polarization and co-culture

After centrifugation and resuspension in a specific medium, THP-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (CS0001, PMA, Multi Science, China). After adjusting for cell density (5 × 105 cells/ml), the final PMA concentration was 100 ng/ml. The cells were planted in six-well plates, with each well supplemented with 2 ml of suspension. After 18 hours of treatment, the differentiation of THP-1 into M0 macrophages was observed under a microscope. M0 macrophages were cultivated in co-culture trials with supernatants from CRC cells that had undergone different treatments. For the next 48 hours of research, the supernatants from macrophages that had undergone different treatments were collected and co-cultured with normal CRC cells.

qRT-PCR

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was extracted from RKO cells that had undergone different treatments. A column-based RNA extraction kit (Code No. 9767, Takara, Japan) was used for this process. An RNA reverse transcription kit (Takara, Japan) was used to create the cDNA, and the LightCycler480 (Roche, Switzerland) was used to amp up the cDNA. Using GAPDH as the internal control, each sample was run three times, and the 2-ΔΔCt technique was used for analysis. The following primers were utilized: GAPDH: forward primer: 5′-AATGGGCAGCCGTTAGGAAA-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC-3′; LAMA1: forward primer: 5′-GTCAGCGACTCAGAGTGTTTG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CTTGGGTGAAAGATCGTCAGC-3′.

Western blot (WB)

Cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (P0013C, Beyotime, China) following two PBS (C0221A, Beyotime, China) washes. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm/min at 4°C after being sonicated. The supernatant was extracted for subsequent experiments. Using SDS-PAGE, equal volumes of protein extracts were separated and deposited onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF, Sangon Biotech, China) membranes. The corresponding antibodies were then incubated overnight at 4°C on the PVDF membranes after they had been blocked for 45 minutes with 5% skim milk. The next day, the membranes were rinsed with PBST and then incubated for 45 minutes with secondary antibodies coupled with horseradish peroxidase. After several PBST washes, the iBright imaging system (Thermo Fisher, USA) was used for analysis and visualization using an ECL chemiluminescence kit (Bio-Rad, USA). The antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-p-AKT antibody (p-Ser473, 4060) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, USA; other antibodies were purchased from Abcam, UK, as listed: rabbit anti-LAMA1 antibody (ab315275), rabbit anti-E-cadherin antibody (ab314063), rabbit anti-N-cadherin antibody (ab76011), rabbit anti-vimentin antibody (ab16700), rabbit anti-AKT antibody (ab179463), rabbit anti-EGFR antibody (ab52894), rabbit anti-p- EGFR antibody (p-Y1045, ab316155), rabbit anti-CREB antibody (ab32515), rabbit anti-p-CREB antibody (p-S133, ab32096), rabbit anti-GAPDH antibody (ab181602), and goat anti-rabbit IgG (ab238531).

ELISA

The Human LAMA1 ELISA kit (ab315073, Abcam, UK) was used to measure the protein expression of LAMA1 in the culture supernatant of control or LAMA1-overexpressing RKO cells. Furthermore, M0 macrophages were cultured with supernatants from RKO cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1. The Human IL-10 ELISA kit (ab100549, Abcam, UK) and the Human Arg1 ELISA kit (ab230930, Abcam, UK) were used to assess the amounts of interleukin (IL)-10 and Arg1 in the supernatant, respectively.

Detection of M2 macrophage polarization

Following 48-hour co-cultivation of the supernatants from RKO cells that had undergone various treatments with M0 macrophages, the cells were rinsed with PBS buffer to remove supernatant and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (P0099, Beyotime, China). After being fixed, the cells were cultured for half an hour in PBS buffer that included 0.1% Triton X-100 (P0096, Beyotime, China) and 5% normal goat serum (Gibco, USA). Then, cells were stained with APC Anti-Human CD206/MMR Antibody (E-AB-F1161E, elabscience, China) and PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Human CD163 Antibody (E-AB-F1298J, elabscience, China), diluted in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells were incubated for 30 to 60 minutes at 4°C in the dark, and then they were cleaned three times with PBS buffer. The FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) was used to measure the percentage of M2 macrophages, and FlowJo software (BD Biosciences, USA) was used for analysis.

Cell apoptosis detection

Using a commercial apoptosis detection kit (Qcbio Science © Technologies, China) and double labeling with PI and Annexin V-FITC in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, cell apoptosis was examined. First, cells that underwent different treatments were gathered in PBS and suspended in 100 μl of binding buffer. After adding 10 μl of propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V-FITC to the binding buffer, the mixture was incubated with the cells for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After that, the samples were put into a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA), and the apoptotic rate was calculated using FlowJo software.

Colony formation assay

Cells treated differently were seeded in 12-well plates (400 cells per well), and the cells were cultivated until colonies could be seen to form. After being fixed for 15-30 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde (P0099, Beyotime, China), colonies were dyed for 30 minutes with 0.5% crystal violet (C0121, Beyotime, China). By using photography to count the colonies, the colony formation rate was determined.

Transwell assay

In the migration experiment, cells that underwent different treatments were resuspended in 200 μl of serum-free culture media at a density of 2 × 104 cells/ml and then transferred to the top chamber of Transwell inserts (Corning, USA). Complete culture medium with 10% FBS was introduced to the bottom chamber at the same time. Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA) at a concentration of 50 mg/ml was diluted to a 1 : 8 ratio with serum-free culture media for the invasion experiment. The upper surface of the Transwell membrane was then covered with 100 μl of the diluted Matrigel, and it was incubated for one to two hours at 37°C. After being collected, the cells were densified in serum-free DMEM medium to a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml. The lower compartment received 500 μl of DMEM medium with 10% FBS, whereas the top chamber received 200 μl of cell suspension. After that, the cells were cultured for a full day. The invading cells on the membrane were then preserved with 75% alcohol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution after the non-transmigrated cells on the membrane’s lower side were removed using 0.5% crystal violet (Beyotime, China). Finally, a microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) was used to take photographs of the chambers, and ImageJ software was used to count the number of cells.

Data analysis

The data are shown as mean ± standard deviation, and each experiment was run in triplicate. Using Student’s t-test to assess group differences, GraphPad Prism 10.0 software was used for statistical analysis. A statistically significant p-value was defined as one that was less than 0.05.

Results

Overexpression of LAMA1 in CRC and its influence on macrophage M2 polarization

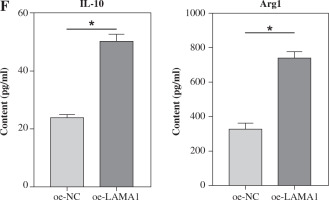

Using qRT-PCR and WB, we first investigated the expression of LAMA1 in human normal colonic epithelial cells NCM-460 and CRC cell lines RKO and LoVo in order to investigate the effect of LAMA1 generated from CRC on macrophage M2 polarization. As seen in Figure 1A, B, CRC cells showed noticeably higher levels of LAMA1 mRNA and protein expression as compared to normal colonic epithelial cells, suggesting that LAMA1 was overexpressed in CRC. The RKO cell line with reduced LAMA1 expression was then chosen for overexpression treatment, and the overexpression efficiency was verified by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1C). Subsequently, LAMA1 secretion levels in each cell culture’s supernatant were measured using ELISA, which showed a substantial increase in secreted LAMA1 upon overexpression (Fig. 1D). Supernatants from CRC cells that were subjected to different treatments were collected for M0 macrophage culture to examine the impact of LAMA1 on macrophage polarization. To measure M2 polarization, the levels of known M2-specific markers (CD206 and CD163) were measured using flow cytometry. The supernatants from CRC cells overexpressing LAMA1 facilitated macrophage M2 polarization, according to the data shown in Figure 1E. Subsequent ELISA analysis showed that treatment with supernatants from CRC cells overexpressing LAMA1 resulted in a substantial increase in the levels of M2 macrophage-associated components IL-10 and Arg1 (Fig. 1F). These results imply that LAMA1 not only overexpresses in CRC cells but also encourages macrophage M2 polarization.

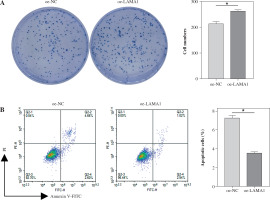

LAMA1 promotes macrophage M2 polarization to aggravate CRC progression

Macrophage M2 polarization promotes malignant advancement in a variety of malignancies, which plays a critical role in carcinogenesis and progression [22-24]. We collected supernatants from CRC cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1 to cultivate M0 macrophages, and then, 48 hours later, we collected the macrophage supernatants to culture normal CRC cells in order to further evaluate whether LAMA1 produced from CRC promotes macrophage M2 polarization contributing to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC. First, tests for colony formation were used to quantify the number of CRC cells in each group that was cultivated using macrophage supernatants. In contrast to the oe-NC group, the results showed that macrophages treated with supernatants from the oe-LAMA1 group increased CRC cell growth (Fig. 2A). Following co-cultivation with macrophages treated with oe-LAMA1 transfected CRC cell supernatants, flow cytometry examination of CRC cell apoptosis revealed a decrease in CRC cell apoptosis (Fig. 2B). The findings of the Transwell assay showed that the migration and invasion capacities of CRC cells were improved by macrophages grown with supernatants from LAMA1-overexpressing CRC cells (Fig. 2C). Additionally, WB examination of EMT pathway marker proteins in RKO cells yielded consistent results, supporting the earlier findings (Fig. 2D) with decreased expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of N-cadherin and vimentin in the oe-LAMA1 group. LAMA1 released by CRC cells further promotes the malignant progression of CRC cells by promoting macrophage M2 polarization.

LAMA1 activates the EGFR/AKT/CREB signaling pathway to influence macrophage M2 polarization

According to previous research, the EGFR signaling pathway plays a crucial role in controlling how macrophages change into the M2 phenotype [25]. Further research is necessary to determine whether LAMA1 additionally accelerates the development of CRC via the EGFR/AKT/CREB signaling pathway. For the rescue studies that followed, we first transformed THP-1 cells transfected with si-NC or si-EGFR into M0 macrophages and co-cultured them with the supernatants of RKO cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1. We next evaluated the phosphorylation state and protein expression levels of EGFR, AKT, and CREB using WB analysis. The findings showed that while the phosphorylation levels of EGFR, AKT, and CREB proteins rose in macrophages after LAMA1 overexpression, there were no appreciable changes in the protein levels of these proteins. On the other hand, following EGFR knockdown, macrophage levels of EGFR protein decreased along with the pathway levels of protein phosphorylation being suppressed. Furthermore, compared to solitary LAMA1 overexpression, simultaneous EGFR knockdown and LAMA1 overexpression prevented increased phosphorylation levels of EGFR, AKT, and CREB in macrophages (Fig. 3A). Following that, each group’s macrophage M2 polarization state was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis. The findings showed that LAMA1 overexpression reversed the tendency of decreased macrophage M2 polarization caused by EGFR knockdown (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the downregulation of IL-10 and Arg1 caused by solitary EGFR knockdown was reversed by the combination treatment of si-EGFR and oe-LAMA1 according to ELISA data (Fig. 3C). These results imply that LAMA1-mediated macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype is significantly influenced by activation of the EGFR/AKT/CREB pathway.

Fig. 1

Overexpression of LAMA1 in colorectal cancer (CRC) and its influence on macrophage M2 polarization. A) qRT-PCR analysis of LAMA1 mRNA levels in NCM-460, RKO, and LoVo cells. B) WB analysis of LAMA1 protein levels in NCM-460, RKO, and LoVo cells. C) qRT-PCR analysis of LAMA1 mRNA levels in RKO cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1. D) ELISA measurement of LAMA1 levels in the supernatant of each cell group. E) Evaluation of macrophage M2 polarization in various cell culture supernatants after culturing with M0 macrophages using flow cytometry; n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; *p < 0.05 F) ELISA measurement of IL-10 and Arg1 levels in the supernatant of M0 macrophages cultured with supernatant from different cell groups. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; * p < 0.05

Fig. 2

LAMA1 aggravates colorectal cancer (CRC) progression by promoting macrophage M2 polarization. A) Colony formation assay to evaluate the proliferation of tumor cells co-cultured with supernatants from oe-NC or oe-LAMA1- transfected RKO cells and normal CRC cells after 48 hours. B) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in tumor cells after co-culture. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; * p < 0.05 C) Transwell assay assessing the migration and invasion capabilities of tumor cells after co-culture, HPF (high power field). D) WB analysis of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin protein expression in tumor cells after co-culture. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; * p < 0.05

Fig. 3

LAMA1 influences macrophage M2 polarization by activating the EGFR/AKT/CREB axis. A) THP-1 cells transfected with si-NC or si-EGFR induced into M0 macrophages and co-cultured with supernatants from colorectal cancer (CRC) cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1, WB analysis of EGFR/AKT/CREB pathway-related protein levels in different macrophage groups. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; *p < 0.05 B, C) Flow cytometry analysis of macrophage M2 polarization in different groups. D) ELISA measurement of IL-10 and Arg1 levels in the supernatants of different macrophage groups. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; *p < 0.05

LAMA1 mediates macrophage polarization via EGFR/AKT/CREB to impact CRC malignant progression

The following tests were carried out to investigate whether LAMA1 exacerbates the malignant evolution of CRC through the EGFR/AKT/CREB signaling pathway-mediated macrophage polarization. To measure the proliferation of CRC cells in each group, colony formation experiments were conducted after THP-1 cells transfected with si-NC or si-EGFR were differentiated into M0 macrophages and co-cultured with the supernatants of CRC cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1. As seen in Figure 4A, CRC cell proliferation was decreased by macrophages co-cultured with si-EGFR in comparison to the oe-NC group, but the proliferative ability of CRC cells was partially recovered by macrophages co-treated with oe-LAMA1 and si-EGFR. Afterward, the various cell groupings’ apoptosis levels were assessed by flow cytometry. The findings showed that the CRC cell apoptosis level in the oe-LAMA1 group was lower than in the control group, that it was higher in the si-EGFR group, and that it was significantly lower in the oe-LAMA1 + si-EGFR group than in the si-EGFR group (Fig. 4B). Transwell tests showed that EGFR knockdown or LAMA1 overexpression in CRC-conditioned medium, respectively, enhanced or inhibited tumor cells’ ability to migrate and invade when engulfed by macrophages. Notably, LAMA1 overexpression-induced improved migratory and proliferation capacities were lessened by EGFR knockdown (Fig. 4C). Macrophages expressing si-EGFR were shown to upregulate the expression of E-cadherin and suppress the expression of vimentin and N-cadherin in co-cultured CRC cells, as determined by WB analysis of EMT pathway marker proteins in RKO cells. On the other hand, this pattern was reversible when macrophages received co-treatment with EGFR knockdown and LAMA1 overexpression (Fig. 4D). The findings indicate that LAMA1 contributes to the malignant development and spread of CRC by mediating macrophage M2 polarization through the EGFR/AKT/CREB signaling pathway.

Discussion

This study showed that CRC cells had higher levels of LAMA1 expression and secretion, which promoted macrophage M2 polarization and improved CRC cell migration, invasion, and proliferation in vitro. Mechanistically, the EGFR/AKT/CREB signaling pathway allowed CRC-derived LAMA1 to drive macrophage M2 polarization. The results of this study provided fresh perspectives on how to improve the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment associated with CRC, identified new targets for preventing cancer from spreading, and created treatment plans.

According to reports, LAMA1 is elevated and has pro-carcinogenic effects in a variety of malignancies, including melanoma [26], pituitary adenoma [27], and choroid plexus papilloma [28]. LAMA1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are important for the development and course of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and may be useful as biomarkers for diagnosis [17]. Moreover, LAMA1 can cause resistance to the targeted medication lapatinib and encourage the growth and migration of HER2-positive brain metastatic breast cancer cells [29]. Nevertheless, it is still unknown how LAMA1 functions in CRC. According to our research, there is increased expression of LAMA1 in CRC, and this overexpression encourages the proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC cells. This discovery, akin to previous research findings, suggests the potential of LAMA1 as a pan-cancer biomarker and targeting LAMA1 as one of the potential strategies for treating CRC.

A growing corpus of studies demonstrates the important role laminin family proteins play in immune control. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer, increased expression of LAMC has been associated with extracellular matrix remodeling and macrophage infiltration, both of which are associated with worse outcomes [30]. By increasing the production of the laminin family protein in exosomes, the overexpression of ETS1 in ovarian cancer cells causes macrophages to polarize M2 [31]. This emphasizes the importance of laminin family proteins in regulating macrophages in the TME, although it is still unknown how CRC-derived LAMA1 and macrophages crosslink. Among the immune cells that are most prevalent in the TME are M2 macrophages. A growing body of research indicates that the complex crosslinks between macrophages and cancer cells might impact the course of cancer in a variety of malignancies, acting as a major catalyst for aggressive traits such as treatment resistance and tumor spread [32]. Tumor cell-derived SPON2 activates PYK2 in CRC to enhance M2 polarization of macrophages, hence influencing tumor development [33]; reports indicate that tumor-derived exosomal miR-934 stimulates M2 polarization of macrophages, boosting liver metastasis in CRC [22]. Similarly, our research shows that LAMA1 generated from CRC promotes the advancement of CRC by inducing macrophage M2 polarization. Our results validate the association between LAMA1 and M2 macrophage polarization, clarifying LAMA1’s pro-carcinogenic pathways and offering a fresh rationale for focusing on LAMA1 to regulate the advancement of CRC.

Moreover, research suggests that EGFR and CREB activation is a crucial mechanism for macrophage M2 polarization [34]. According to studies, REG4 released by pancreatic cancer promotes the advancement of pancreatic cancer by activating CREB and EGFR/AKT phosphorylation [35, 36]; breast cancer cells in an acidic TME create lactate through Zeb1 overexpression, which activates the PKA/CREB signaling pathway and causes M2 macrophage activation [37]. These results imply that suppressing EGFR and CREB activation on a regular basis may be a useful strategy for blocking M2 macrophage polarization. Notably, the EGFR/AKT signaling pathway can be activated by laminin family proteins or their cleavage fragments acting as EGFR ligands [38, 39]. After conducting more research, we discovered that administering LAMA1 to macrophages causes an increase in EGFR, AKT, and CREB phosphorylation. This results in the induction of M2 polarization in macrophages and facilitates the proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC cells. Thus, we propose that LAMA1 generated from CRC at least partially activates the EGFR/AKT/CREB signaling pathway to cause M2 polarization of macrophages. One possible tactic to enhance the immunosuppressive microenvironment in CRC is to target LAMA1.

Fig. 4

LAMA1-mediated M2 polarization via EGFR/AKT/CREB influences colorectal cancer (CRC) malignant progression. A) THP-1 cells transfected with si-NC or si-EGFR induced into M0 macrophages, co-cultured with supernatants of CRC cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-LAMA1, colony formation assays to evaluate proliferation of co-cultured tumor cells. B) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in co-cultured tumor cells. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; *p < 0.05 C) Transwell assessment of migratory and invasive capabilities of co-cultured tumor cells, HPF (high power field). D) WB analysis of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin protein expression in co-cultured tumor cells. n = 3 independent replications of the experiment; *p < 0.05

While our study analyzed the underlying processes and showed that CRC-derived LAMA1 may induce M2 polarization of macrophages and enhance CRC development, there are several elements that need further thorough research. First, it is unknown whether LAMA1 or its cleavage fragments attach to EGFR and then trigger downstream signaling pathways. Second, our results have not been confirmed by in vivo animal models, and the relationship between LAMA1 expression and clinical pathological characteristics and staging in CRC patients has to be further clarified. Thus, to establish a stronger theoretical foundation for the identification of therapeutic targets in the treatment of CRC, we plan to investigate the molecular processes by which LAMA1 controls macrophage M2 polarization and stimulates the growth of cancer in more detail in future research.