Introduction

North-eastern Poland is an endemic region for tick-borne diseases, especially Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis. However, other tick-borne diseases, such as anaplasmosis or rickettsioses, can also occur. Spotted fever is a tick-borne vector disease caused by small, gram-negative bacteria (0.3-0.5; 0.8-2.0 μm). Currently, over 30 different species of Rickettsia are known. The course of the disease is characterized by a nonspecific clinical picture, and infection occurs after a tick bite. The average incubation period following a tick bite is 3 to 12 days. Symptoms most commonly include a sudden onset of fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, and a fine spotted or pustular rash. A black scab or ulcerative skin lesion may also appear at the site of the tick bite. The course of spotted fever is usually mild. With proper diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis is favorable. It should be noted that isolated cases of spotted fever may also occur in non-endemic countries, and this disease entity should be considered in patients with the clinical features described above [1-5].

Tularemia is an infectious disease caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis, whose main reservoir is wild animals, especially rodents. Humans can become infected through contact with animals, contaminated water and food, as well as through the bite of insects, including ticks. Currently only 4 subtypes have been described; in Europe the more common one is subtype B. The incubation period lasts an average of 3-5 days, but symptoms can occur even after 15 days. The main symptoms are not very specific and include general weakness fever, chills, and myalgia. However, it is possible to distinguish 6 characteristic clinical forms. The most common one is the ulcero-glandular form, which is a small nodule with a livid infiltrate and an ulcerating pustule and painful enlarged lymph nodes. This form usually has a benign course [6, 7]. Immunoserological and polymerase chain reaction methods play a key role in the diagnosis of both pathogens.

Ticks can act as a vector for multiple pathogens. Some studies suggest that co-infection with tick-borne pathogens may affect the course of the disease, the appearance of atypical symptoms, prolongation of disease duration and response to the therapy provided. The exact mechanism of co-infection is not entirely understood. Therefore, this phenomenon requires further research and should be considered in the diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases [8, 9].

We present a rare case of Rickettsia spp. and F. tularensis co-infection in a 46-year-old female patient, confirmed by serological and molecular tests.

Case description

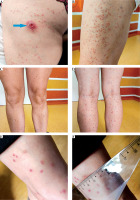

A 46-year-old female patient from north-eastern Poland, with no history of travel and no chronic diseases, was admitted to the hospital due to fever, an ulcer on the left lower extremity, and a rash that initially appeared on the left thigh and spread to the upper limbs and trunk. She reported a tick bite three weeks before hospitalization. The symptoms appeared 5-7 days after the tick bite and lasted for 2 weeks. On physical examination, a maculopapular rash over the entire body, an ulcer on the left lower extremity, and an enlarged inguinal lymph node were noted (Fig. 1). Laboratory tests showed a moderate increase in inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein [CRP]: 32.85 mg/l, white blood cells [WBC]: 12 400/μl). Markers for autoimmune diseases (e.g. ANA, ASO, c-ANCA, p-ANCA, anti-DNP) were negative. Screening serological tests excluded human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections. Electrocardiogram (ECG), chest X-ray, and echocardiography revealed no abnormalities. Empirical treatment with ceftriaxone and amikacin was initiated. After 7 days of antibiotic therapy, no clinical improvement was observed. Spotted fever and tularemia were suspected, and further diagnostics were conducted . Rickettsia spp. DNA was detected by PCR in eschar swab samples and an ulcer smear. Anti-Rickettsia typhi IgG antibodies (1 : 128, positive), anti-Rickettsia rickettsii Spotted Fever Group antibodies IgG (1 : 256, highly positive), and anti-Francisella tularensis IgG and IgA antibodies were detected by immunoserology in the serum (Table 1). Ceftriaxone 2 g/day and amikacin 1 g/day for 1 week showed a low response. The treatment was changed to doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 14 days, with reduction of the visible rash observed after 5-7 days and full recovery after 14 days. She recovered completely with no complications.

Discussion

We present to our knowledge the first case of Rickettsia spp. and F. tularensis co-infection confirmed by PCR (Rickettsia spp.) and serological tests (Rickettsia spp. and Francisella tularensis) from north-eastern Poland. This finding is of high importance, especially as rickettsiosis and tularemia are not common diseases in Poland, and co-existence of these two diseases is even less common. It is known that serological tests, like all diagnostics methods, have some limitations. They were useful in our case, and the patient recovered completely after the treatment was changed upon receiving the results of tests.

Data on co-infection with both pathogens are scarce. Chmielewski et al. studied the sera of 36 patients with skin changes and lymphadenopathy in whom SFG (spotted fever group rickettsioses) or F. tularensis was confirmed. They found high titers of antibodies against Rickettsia spp. in 4.4% (1 patient with tularemia) and high antibody titers against F. tularensis in 6.7% (1 patient with SFG), suggesting co-infection with both bacteria in 5.5% of subjects [10]. To date, coinfection of Rickettsia ssp. and F. tularensis has been described in ticks [11, 12] and reservoir animals (Rattus rattus, Clethrionomys glareolus and Microtus arvalis) [13, 14].

We hypothesize that the emergence of coincident cases of both pathogens in humans and mammals in Central European countries may be related to global warming and migratory behavior of wild birds on a northbound route from wintering areas in Africa which carry ticks. Hoffman et al. confirmed the highest number of infected ticks in birds migrating from wintering grounds to breeding grounds in Poland (e.g. Saxicola rubetra, Sylvia atricapilla, Ficedula hypoleuca) [15, 16].

The drug of choice for Rickettsia spp. infections is doxycycline, while the drugs of choice for severe F. tularensis infections are aminoglycosides (streptomycin and gentamicin), and for mild infections are fluoroquinolones and doxycycline. In the case of resistance to the above-mentioned drugs, chloramphenicol can be used [17]. Chmielewski et al. [10] successfully treated patients with mixed infection with doxycycline; therefore, we decided to use this treatment in our patient. The use of doxycycline significantly improved our patient’s clinical condition, which shows that this antibiotic is effective for F. tularensis/Rickettsia spp. co-infection.

Given the potential for increasing numbers of patients with these diseases, our case provides healthcare professionals with valuable insights they can use in the diagnosis of patients after a tick bite.

Table 1

Results of basic laboratory, serological, and molecular tests

Conclusions

Rare diseases such as rickettsiosis and tularemia should be included in the differential diagnosis of fever, lymphadenopathy, and skin changes after a tick bite.

Co-infection with Rickettsia spp. and Francisella tularensis is possible in patients after a tick bite. Quick diagnosis influences proper treatment and complete recovery.