Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a pregnancy complication that develops during the second or third trimester of pregnancy and is not caused by preexisting type 1 diabetes (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [1]. GDM is now one of the most prevalent pregnancy disorders, with an increased frequency in many countries throughout the world, ranging from 1% to 22% depending on the population evaluated and the diagnostic criteria [2-5]. Moreover, GDM is associated with an increased risk of complications for both the mother (e.g., increased risk for pre-eclampsia, T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases) and the fetus (e.g., T2DM, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, and allergic disorders) [6-10].

Gestational diabetes mellitus is a pathology characterized by a chronic low-grade inflammation [1]. The presence of inflammatory cytokines leads to insulin resistance [2] and endothelial dysfunction [3, 4], favoring the occurrence of post-GDM complications.

Recent evidence suggests that GDM is identified not only by elevated insulin resistance and glucose intolerance but also by enhanced systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation, resulting in an imbalance between T-helper 1 (Th1) and T-helper 2 (Th2) cells, favoring pro-inflammatory responses [11, 12].

Additional T-cell subsets, on the other hand, are known to be involved in the control of the immune response in a variety of diseases, including pregnancy complications [13-15]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) may have a key contribution to maintaining tolerance in peripheral tissues and peripheral blood, comprising 5-15% of the subpopulation of peripheral CD4+ T lymphocytes [5, 6]. Tregs were found to be the key immune cells that contribute to induction and enhanced maternal tolerance via controlling inflammatory reactions in response to the antigens of the fetus [7]. These cells act by contacting target cells via cell surface molecules, e.g. cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein-4 (CTLA-4), and glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related protein (GITR), and secreting cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-10, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and IL-35 [6, 8-12].

Th17 cells contribute to adverse inflammatory responses during pregnancy via secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-22, IL-21, IL-17A, IL-17F, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [13-15]. Th17 cells are one of the cell subsets that are regulated by Tregs [13-15]. IL-23 and IL-6 are mainly secreted by innate immune cells [13-15]. The imbalance of the Treg/Th17 axis is a key contributor to the occurrence of several pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia-recurrent abortion [10, 16-28]. Inflammatory reactions were shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of GDM [29, 30]. Increased frequency of Th17 cells in the third trimester in GDM women suggested an enhanced pro-inflammatory condition in GDM women [29]. Therefore, an imbalance between Tregs and Th17 cells in women with GDM leading to enhancing inflammatory reactions could cause GDM [29].

The frequency of Th17 cells was higher in women with GDM, which may indicate more pronounced pro-inflammatory circumstances in these individuals. Consequently, GDM may result from an imbalance between Tregs and Th17 cells, which would intensify inflammatory responses.

Curcumin is a natural component that is derived from the rhizomes of Curcuma longa with antioxidant, pro-apoptotic, anti-proliferative, chemotherapeutic, and anti-microbial properties [30-35]. Accumulating evidence shows that curcumin acts as a unique immunomodulatory agent in a broad range of disorders with unregulated immune responses [36, 37]. The immune-modulatory effects of curcumin at the molecular and cellular levels have been demonstrated in the control of the immune system [38, 39].

Additionally, curcumin inhibits the activation of STAT3 signaling, demonstrating significant anti-inflammatory functions [2, 39].

One of the immunomodulatory effects of curcumin is balancing the Treg/Th17 axis in several inflammatory diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and diabetes type 2 [38-40]. Our knowledge of how curcumin affects the Treg/Th17 axis in GDM has not been studied yet. We designed the present study to evaluate the impacts of curcumin on the percentage of Tregs and Th17 cells and the related cytokines (IL-10, IL-6, and IL-17A) in PBMCs from women with GDM in comparison to controls.

Material and methods

Subjects

This was a case-control study that was conducted from 2019 to 2021 on 50 pregnant women with GDM (the case group) in the third pregnancy trimester and 50 non-pregnant women (the control group) in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the People’s Hospital of Deyang City. The study process was presented to the participants, who gave their informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. A form was filled out with general demographic information, socioeconomic status, parity, family history of diabetes and/or hypertension and historical history of GDM, as well as a history of hospitalization and/or urinary tract infection during the current pregnancy. A positive result in the blood HCG tests showed pregnancy. All subjects in the two groups were in the third trimester of pregnancy (between the 28th and 34th gestation week). Age and body mass index (BMI) were matched in the two studied groups. Only primigravida women without diabetes type 2 were included in this study. For diagnosis of diabetes type 2 the below laboratory results were considered:

Symptomatic women with random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl, fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%, 2 h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl [41].

For screening GDM, the 2 hours 75 g OGTT in the morning after overnight fasting was done [41]. GDM was diagnosed when fasting plasma glucose was ≥ 92 mg/dl, or 1-h OGTT plasma glucose was ≥ 180 mg/dl, or 2-h OGTT plasma glucose was ≥ 153 mg/dl [24]. Women with GDM had regular glucose monitoring with a good diet. Alcohol drinking, smoking, diagnosis of diabetes type 2, another systemic/inflammatory disease (including, food allergy), psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, rhinitis, atopy, asthma and autoimmune thyroidopathies, other autoimmune diseases and history of any prescribed medications within the last one year were the exclusion criteria for studied subjects. The requirement of insulin treatment or any other treatment that could affect the studied parameters and the development and diagnosis of other complications during pregnancy were the withdrawal criteria during the study. Controls had normal plasma glucose levels. The inclusion criteria for the controls were normal results in the routine laboratory test panel (as mentioned above).

Laboratory experiments

Blood samples and serum collections. Isolation of PBMCs from 10 ml of peripheral venous blood was done via Ficoll, lymphosep (Biosera, UK). 106 cells/ml were cultured in media in RPMI-1640 (phosphate-buffered saline, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). PBMC culture (2 × 105/ml of media) was done in the presence of various doses of curcumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) (1 μM, 6 μM, 12 μM, 100 μM), and 0 (control) for 72 hours as described previously [41]. DMSO was used for dissolving curcumin.

After collection of the whole blood, the blood was allowed to clot at room temperature (15-30 min). The clot was removed by centrifuging at 1000-2000 × g for 10 min in a cooled centrifuge. The serum supernatant was collected.

Cell culture

For the experiments, sets of 1 × 106 PBMC/patient or control were placed in each well of sterile polystyrene plates. For each subject (in the case and the control group), there were 4 experiments on uncultured or fresh PBMCs, curcumin-treated PBMCs (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA, 1 μM), phytohemagglutinin (PHA, 10 μM) (as the positive control), or with the media only (as the negative control or no treated cells).

Flow cytometry assessment

Treg staining was performed using a Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For experiments, the PBMCs were first labeled with anti-human CD4 (FITC-conjugate), anti-human CD25 (PE-conjugate), CD127 (APC-conjugate) (3 antibodies from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). For this, 1 × 106 cells were first incubated with 10 μl of each antibody at 4°C in the dark for 30 minutes then washed with staining buffer. After that, the cells were fixed in 0.5 ml of fixation buffer after being permeabilized with 0.5 ml of permeabilization buffer. After staining for surface markers, intracellular staining with anti-human Foxp3 (PE-Cy5-conjugate; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) was performed for 30 minutes at 4°C.

For detection of the frequency of Th17 cells among PBMCs, the cells (1 × 106) were cultured with 50 ng/ml PMA and 1 μg/ml ionomycin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), for 4 to 5 hours in the presence of brefeldin A (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2, for intracellular cytokine production. After stimulating the cells for 4 to 5 hours, cell surface staining was performed with anti-CD3 conjugated with PECy5 and anti- CD8 conjugated with FITC (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). The cells were fixed/permeabilized using the appropriate buffers according to the manufacturer’s protocol (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), and intracellular staining was performed using anti-IL-17 conjugated with PE or isotype control (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) in the dark.

The stained cells (1 × 105 cells for each sample) were immediately analyzed in the FACSCalibur system. Data were analyzed using the Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

ELISA

The concentration of cytokines was measured by ELISA kits (BioLegend, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell culture supernatants were collected after 72 hours and were assayed for concentrations of soluble IL-10, IL-6 and IL-17A; all samples were run in duplicate. The sensitivity of each assay was as follows: 0.8 pg/ml (IL-17A), 1.6 pg/ml (IL-6) and 3.5 pg/ml (IL-10).

Analysis of statistics

SPSS 16.0 and Prisma.8 software was used for data analysis. ANOVA and parametric/non-parametric T-tests were used for data analysis. P-values of less than 0.05 were regarded as significant. The data are presented as mean ± SE.

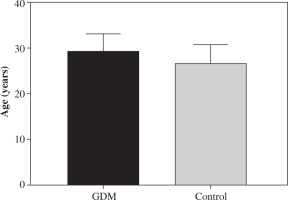

Fig. 1

Age difference between women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and the controls. There was no significant difference in the mean age of women with GDM and the controls. The mean age in the control women was 26.22 ±4.5 years (range 24-30 years). The mean age in women with GDM was 28.92 ±3.9 years (range 25-31 years). Data are expressed as mean ± SD

Results

There was no significant difference in mean age between the control group and women with GDM (p > 0.05; Fig. 1). Clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

Optimization concentration of curcumin for cell culture

The toxicity of curcumin in a culture of PBMCs was evaluated by the rate of apoptosis in various doses of curcumin (0, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM) in the presence of Th17 differentiation stimulators (PMA-ionomycin), which was described in the previous study [37]. The viability of cells changed in a dose-dependent manner after treatments with curcumin. In the presence of a low dose of curcumin (0.1 and 1 μg/ml), the cell viability did not change significantly compared to its absence (0 μg/ml). 1 μg/ml dose of curcumin was selected for cell culture experiments.

Table 1

Clinical and demographic characteristics of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) patients and controls

Effects of curcumin on the percentage of Th17 cells

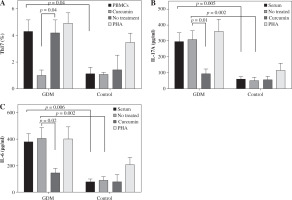

The percentage of Th17 cells in women with GDM was significantly higher compared to the control group (4.30 ±0.85 vs. 1.13 ±0/46, p = 0.04; Fig. 1A). The percentage of Th17 cells decreased after treatment with curcumin relative to untreated cells in the GDM group (1.02 ±0.35 vs. 4.2 ±0.94, p = 0.04; Fig. 1A).

Effects of curcumin on levels of IL-17 and IL-6 as pro-inflammatory cytokines

Serum level of IL-17A as the main secretory cytokine of Th17 cells and serum level of IL-6 as the major cytokine involved in the differentiation of Th17 cells were higher in women with GDM (295.2 ±54.1 pg/ml vs. 58.4 ±13.3 pg/ml, p = 0.005, and 378.30 ±63.05 pg/ml vs. 78.01 ±21.02 pg/ml, p = 0.006; Fig. 2B, C). In the GDM group, IL-17A concentrations in cell culture supernatants were considerably higher than in the control group (306.02 ±57.02 pg/ml vs. 48.10 ±20.4 pg/ml, p = 0.002; Fig. 2B). The IL-6 level in cell culture supernatants was also significantly higher in women experiencing GDM than the control group (408.45 ±79.46 pg/ml vs. 88.83 ±29.20 pg/ml, p = 0.002; Fig. 2C).

Curcumin reduced the IL-17A level in the GDM group (92.05 ±27.9 pg/ml vs. 306.02 ±57.02 pg/ml, p = 0.01; Fig. 1B). Curcumin treatment reduced the IL-6 level only in the GDM group (145.20 ±35.50 pg/ml vs. 408.45 ±79.46 pg/ml, p = 0.02; Fig. 1C), and not in the control group.

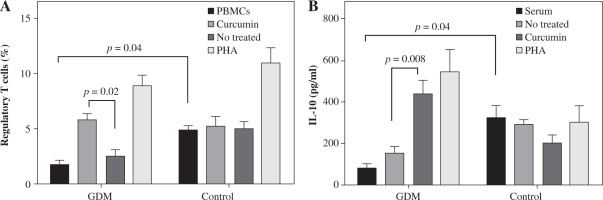

Effects of curcumin on the percentage of Tregs

It was observed that curcumin may affect the percentage of Tregs as the master regulators of inflammation. The frequency of Tregs decreased in untreated GDM in comparison to untreated control PBMCs. Otherwise, treatment with curcumin enhanced the percentage of Tregs when compared with untreated PBMCs in the GDM group (5.9 ±0.48 vs. 2.65 ±0.46, p = 0.02; Fig. 2A) but not in the control group (5.35 ±0.76 vs. 5.03 ±0.65, p > 0.05; Fig. 2A). PHA was used as a positive control.

Effects of curcumin on levels of IL-10 as an anti-inflammatory cytokine

In women with GDM, the serum level of IL-10 decreased significantly relative to the healthy women (83.01 ±18.02 vs. 328/4 ±54.04, p = 0.04; Fig. 3B). In the presence of curcumin, the IL-10 level in the cell culture supernatants was significantly higher in the GDM group compared to the negative control (untreated cells) (447.72 ±59.50 vs. 157.98 ±26.50, p = 0.0008; Fig. 3B).

Discussion

Gestational diabetes mellitus is a transitional pregnancy disorder with insulin resistance that may result from a breakdown in the balance of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses during pregnancy [42]. Additionally, the hyperglycemic condition caused a pro-inflammatory state characterized by alteration of the cytokine profile in the peripheral blood, and in the decidua in women with GDM [43]. However, the immunological mechanisms behind GDM are still poorly understood. Alterations of frequencies of T cell populations were observed in women with this disease, which are likely to negatively impact maternal tolerance [25].

Fig. 2

Effects of curcumin on frequency of Th17 cells and levels of IL-17A and IL-6 in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and the controls. PBMCs from patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (n = 50) and normal controls (n = 50) were cultured in the presence of curcumin (6 μM) or PHA (10 μM) for 72 hours for each experiment. PHA was used as the positive control. PBMCs that were cultured in the media only were used as the negative control. The FACSCalibur system was used for the flow cytometry assessment of Th17 cells, and the data were analyzed by FlowJo software. ELISA was used for the measurement of IL-17A and IL-6 levels in serum and supernatants. Data are expressed as mean ± SE. A) Frequency of IL-17-producing PBMCs after PMA/ionomycin stimulation. B) ELISA of IL-17A production in serum and supernatants. C) ELISA of IL-6 production in serum and supernatants

Treg/Th17 imbalance may be a causative factor in pregnancy disorders with an inflammatory etiology, e.g. spontaneous abortion, and preeclampsia [44-47]. The current study found that the proportion of Th17 cells was elevated, while the percentage of Tregs was decreased, in PBMCs from women with GDM, demonstrating that Treg/Th17 imbalance may be involved in the immunopathogenesis of GDM.

Fig. 3

Effects of curcumin on frequency of Tregs and IL-10 levels in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and controls. PBMCs from patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (n = 50) and normal controls (n = 50) were cultured in the presence of curcumin (6 μM) or PHA (10 μM) for 72 hours for each experiment. PHA was used as the positive control. PBMCs that were cultured in the media only were used as the negative control. The FACSCalibur system was used for the flow cytometry assessment of Tregs, and the data were analyzed by FlowJo software. ELISA was used for the measurement of IL-10 levels in serum and supernatants. Data are expressed as mean ±SE. A) Quantitative analysis of frequency of Tregs. B) ELISA of IL-10 production in serum and supernatants

Tregs, a subpopulation of T CD4+, regulate the unfavorable inflammatory reactions against antigens of the fetus that are induced by Th17 cells. This makes them a valuable choice for cell-based immunotherapy in pregnancy disorders [44, 48]. Women with GDM were shown to have dysfunctional and/or low frequency of Tregs in circulation and/or in decidua [30, 49]. Lower frequency of Tregs was found to be associated with higher blood sugar and lipoprotein density in GDM compared to healthy pregnant women [42].

Treg function may be disturbed due to epigenetic alterations of metabolic pathways in GDM [10]. This may result in increased expression of immune checkpoint molecules on the surface of Tregs that was found in GDM [10]. Additionally, the lower number of Tregs in the human placenta along with downregulation of the receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANK) was found in women with GDM [10]. However, a higher percentage of Tregs in peripheral blood in those women compared to healthy pregnant women was also reported [10]. Therefore, it is likely that Treg counts may change depending on the trimester and be influenced by metabolic anomalies in GDM [10].

In this study, we demonstrated that serum levels of IL-10 were significantly lower in women with GDM than the healthy women. IL-10 as the anti-inflammatory cytokine plays the main role in the regulation of inflammatory reactions against antigens of the fetus to induce maternal tolerance [48-51]. It was found that IL-10 expression was up-regulated in cytotrophoblasts and decidual T cells during successful pregnancy, while downregulation of IL-10 expression in PBMCs was observed in patients with GDM [52]. Additionally, it was found that GDM patients have lower levels of IL-35, a newly discovered immunosuppressive cytokine produced by Tregs [52].

The current study showed that serum levels of IL-17A and IL-6 were higher in those patients than in controls. Inflammation has already been identified as the main contributor to inflammatory disorders and pregnancy complications including recurrent abortion preeclampsia and GDM [44, 53-55]. IL-17A is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that may play a part in the immunopathogenesis of GDM via triggering inflammatory reactions and enhancing the infiltration of neutrophils in the decidua tissue [28, 30, 56]. This may generate a positive feedback loop that intensifies inflammatory responses [57, 58]. Other pro-inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathophysiology of GDM [59]. Elevated serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, which might influence the recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils to adipose tissue, were reported in GDM [60, 61]. Furthermore, the prevalence of Tregs was found to be negatively correlated with the blood levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in GDM [61]. Therefore, our findings confirmed the results of the mentioned studies suggesting that Th17/Treg imbalance may play a role in the immunopathogenesis of GDM.

Curcumin, a natural substance that depends on the dose, target cells, and the physiological and pathological context, may have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-parasitic, antispasmodic, and anti-cancer properties [44]. It has been found to improve metabolic disorders including diabetes by controlling oxidation and inflammatory processes [62]. In the context of GDM, the impacts of curcumin on reproductive outcome and oxidative stress were evaluated in experimental models [44, 63].

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls cellular energy under conditions of cellular stress [64]. In this scenario, ATP use by the cells activated AMPK and replenished the cellular ATP levels in a cell-autonomous mechanism [65]. It was also demonstrated that activating AMPK improved maternal condition, reduced GDM, and promoted fetal growth [64]. AMPK could be used as a pivotal biomarker for GDM diagnosis and prognosis. Interestingly, curcumin (100 mg/kg, oral gavage every day) was found to promote AMPK activation, resulting in alleviating GDM [44]. Enhanced AMPK activation was associated with decreased HDAC4 (histone deacetylases-4) and G6Pase expression in an experimental model of GDM [44]. HDAC4 modulates the endocrine function and glucose homeostasis in various tissues. Curcumin also effectively improved the birth weight of GDM mice by restoring the intolerance of insulin and glucose [44]. Curcumin decreased thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) expression and increased glutathione, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase expression in GDM mice [44]. Those markers are related to oxidative stress; therefore, curcumin may alleviate oxidative stress in GDM.

For the first time, the current study evaluated the effects of low doses of curcumin on the Treg/Th17 axis on PBMCs from women with GDM. The idea for designing this research came from the works on the effects of curcumin on the Th17/Treg axis in diseases with inflammatory etiology. Treg/Th17 imbalance may be involved in the pathogenesis of GDM and autoimmunity. It was observed that curcumin acted as a modulator of the immune responses through balancing the Treg/Th17 axis in auto-immune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, diabetes and ulcerative colitis (UC), which share similar inflammatory pathology with GDM [66]. Administration of low doses of curcumin (0.1 and 1 μg/ml) could reduce the production percentages of Th17 and IL-17A. Curcumin also increased the percentage production of Treg and TGF-β1 in CD4+ T cells from patients with SLE [66]. A clinical trial indicated that curcumin relieved pain and modulated the Th17/Treg axis in patients with osteoarthritis. Curcumin decreased the Visual Analog Score (VAS), numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and frequency of Th17 cells in those patients. Additionally, administration of curcumin (Sinacurcumin 80 mg daily for 3 months) increased the Treg/Th17 cell ratio [67]. Another clinical trial demonstrated that after treatment with nanocurcumin in osteoarthritis, patients showed a meaningful increase in frequency of Tregs and expression of miR-146a and FoxP3 gene expression [68]. MiR-146a is one of the miRNAs prevalently expressed in Tregs and is necessary for the suppressive function of Tregs [69]. FoxP3 is the specific transcription factor of Tregs that is related to the function and development of Tregs [70]. Treatment with nanocurcumin enhanced levels of IL-10 and TGF-β, and it lowered IL-6 secretion in osteoarthritis patients [68]. Nanocurcumin was found to reduce Th17-associated parameters, including frequency of Th17 cells and reti- noic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor γ (RORγt) expression [66].

In diabetic mice with ulcerative colitis, curcumin (100 mg/ kg/day) significantly improved the symptoms of diabetes, with a lower insulin level, heavier weight, and less inflammatory cell infiltration. Curcumin-treated mice showed attenuated Th17 responses and enhanced Treg function. Curcumin effectively alleviated colitis in mice with type 2 diabetes mellitus by restoring the homeostasis of Th17/Treg and improving the composition of the intestinal micro-biota [71].

For the first time, the current study evaluated the effect of low doses of on Treg/Th17 balance in GDM. Curcumin increased Treg frequency and decreased the proportion of Th17 cells in PBMCs from women with GDM. Curcumin improved the percentage of Tregs along with reducing production of Th17 cells in vitro in women with GDM. Curcumin treatment diminished the levels of IL-6 and IL-17A in supernatants of PBMCs from women with GDM. It also increased levels of IL-10 in vitro. Therefore, we propose that a low dose of curcumin may act as an immunomodulatory component in reducing the risk of GDM through elevating anti-inflammatory responses.

Concluding remarks

The current study showed that unbalanced inflammatory responses might play a role in GDM. This research included in vitro experiments evaluating the influence of curcumin on PBMCs; none of the subjects were taking any curcumin supplementation.

The number of Tregs decreased, while the proportion of Th17 cells increased in women with GDM. Curcumin modulated the immune responses via balancing of Treg/Th17 in women with GDM. Curcumin increased IL-10 levels, while it decreased the levels of IL-6 and IL-17 in supernatants of cell culture in women with GDM. Curcumin may regulate macrophages and dendritic cells as important producers of IL-6 [12]. We propose that future studies need to focus on evaluation of the probable impacts of curcumin on the innate responses. Curcumin increased IL-10 levels, while it decreased the levels of IL-6 and IL-17 in supernatants of cell culture in women with GDM. In summary, curcumin served as an immunoregulatory (by increasing Treg activity) and immunosuppressive (by reducing Th17 cell function) component to reduce the risk of GDM. However, the findings need to be validated by clinical trials.

It is worth noting that administration of any supplement during pregnancy needs to be carefully evaluated due to the contradictions in pregnancy and probable adverse effects on the fetus. Thus, future clinical studies investigating the effects of curcumin on GDM must employ a cautious approach and be performed within an appropriate framework.