Introduction

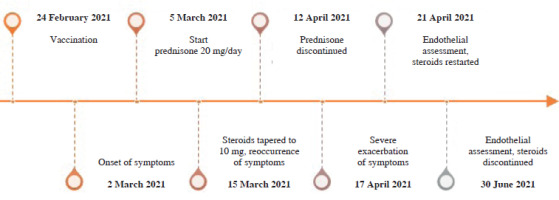

Here, we describe the case of a young woman who developed incomplete systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS) after COVID-19 vaccination. A 30-year-old healthy woman with no medical record was vaccinated with AstraZeneca adenovirus vector vaccination (currently Vaxzevria). Six days after vaccination, generalized urticaria occurred. Malaise, fatigue, arthralgia, and myalgia had emerged gradually as prodromal symptoms over the six days following vaccination. She presented to the rheumatology clinic, and a short course of 20 mg of prednisone daily was started, which provided rapid resolution of symptoms. However, the decrease in the glucocorticosteroid dose to 10 mg caused exacerbation in the form of edema of the hands and feet, cold limbs, notable general edema of the subcutaneous tissue, and a drop in blood pressure. Her parameters were: 105/69 mmHg, 90/min, BMI 23.5 kg/m2. Her regular blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg. Physical examination was unremarkable apart from generalized subcutaneous edema. Complete blood count, creatinine, and urinalysis were normal, but there were elevated levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, transaminases, hypoalbuminemia, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Immunofixation and free light chains assays were normal, ruling out monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). The anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody concentration was high and active infection was ruled out by polymerase chain reaction. Oral swab, blood, and urine cultures were negative. Active infection with viral hepatitis A, B, C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and Borrelia ssp. was excluded. No anti-nuclear antibodies or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were detected. By the association of generalized subcutaneous edema, relative hypotension, and hypoalbuminemia without albuminuria, the diagnosis of vaccination-induced forme fruste of SCLS was made. The patient’s condition was stable enough to forgo the use of intravenous fluids or vasopressors, allowing for treatment on an outpatient basis. The daily dose of 20 mg of prednisone was restarted and tapered slowly over two months, leading to resolution of symptoms. The timeline of events is detailed in Figure 1. The second dose of vaccination was delayed, and the patient was vaccinated 9 months after the end of treatment, with no adverse effects. She remains healthy.

Discussion

We searched the Scopus, Web of Science and MEDLINE databases using the keywords ‘edema’, ‘systemic capillary leak syndrome’, ‘Clarkson disease’, ‘endothelial function’, ‘endothelial dysfunction’ and ‘vaccination’ or ‘immunization’ or ‘vaccine’. Here, we discuss individual well-described cases published as detailed case reports or case series (summarized in Table 1). In primary idiopathic form, SCLS is known as Clarkson disease. Only a few hundred cases have been reported, with high rates of accompanying MGUS. This pattern is observable in cases of SCLS related to COVID-19 immunization. A case series by Matheny et al. presented three cases of exacerbation of SCLS caused by COVID-19 vaccination: one patient had SCLS with MGUS diagnosed 15 years before vaccination with Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen), the second had a history of an SCLS episode attributed to sepsis prior to vaccination with the second dose of the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna), and the third had a history of syncope and seizures prior to receiving the second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) [1]. Another patient, a 36-year-old man who developed SCLS after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Janssen), had a history of plasmocytic dyscrasia (smoldering multiple myeloma) and a possible flare of SCLS in the medical record that was retrospectively assumed [2]. Robichaud et al. described a patient with similar clinical characteristics, a 66-year-old male patient with SCLS onset two days after ChAdOx1 nCOV-19 vaccination (AstraZeneca). He had a history of monoclonal gammopathy (immunoglobulin G kappa) and a potential episode of SCLS in the past [3]. A woman in her 40s was found to have MGUS IgG lambda during SCLS diagnostic work-up triggered by the COVID-19 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) [4]. The third patient who developed SCLS after the second dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) was a 38-year-old man with clonality findings of IgA and IgG kappa during diagnostic workup and a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test [5]. SCLS was reported in combination with exacerbation of generalized pustular psoriasis after the second dose of mRNA vaccination [6]. A milder case of a 46-year-old woman who developed generalized edema and pseudothrombocytopenia was also reported, but with normal blood pressure and no hypoalbuminemia and hemoconcentration 12 days after the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine [7]. The clinical manifestation of this woman resembled our patient the most, suggesting another example of incomplete SCLS with no life-threatening course but with generalized edema and transient systemic inflammation. SCLS may be triggered not only by COVID-19 vaccination but also by SARS-CoV-2 infection itself [8]. Thus, it remains to be determined whether episodes of SCLS are triggered by adenoviral vectors, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, or other factors such as recent viral infections with other viruses, medications, or genetic susceptibility. Treatment of life-threatening manifestations of idiopathic SCLS primarily focuses on acute management of respiratory and circulatory support. In hypovolemic patients, intravenous crystalloids and occasionally colloids are cautiously used along with vasopressors. There is no established therapeutic standard for SCLS, and treatment is largely based on clinical case series [9]. Steroids are used empirically, but conclusive data supporting their efficacy are lacking. The present patient had an incomplete manifestation of SCLS and did not require organ support. She responded well to glucocorticosteroids.

Table 1

Characteristics of systemic capillary leak syndrome after COVID-19 vaccination

| Article | Age | Sex | Vaccine type | Vaccine dose | Prior SCLS | Plasmocytic dyscrasia | Other factors | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokel et al. [7] | 46 | F | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford – AstraZeneca) | First | No | No | Pulmonary emphysema, pseudothrombocytopenia | GCs | Recovery |

| Buj et al. [5] | 38 | M | BNT162b2 (mRNA) (Pfizer-BioNTech) | Second | No | MGUS IgG and IgA Kappa | Positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 | Supportive care at ICU | Recovery |

| Choi et al. [2] | 36 | M | Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Janssen) | First | Likely | Smoldering multiple myeloma | No | Fluids, antibiotics, inotropes | Fatal |

| Inoue et al. [4] | 40 | F | BNT162b2 (mRNA) (Pfizer-BioNTech) | Second | No | MGUS IgG Lambda | No | Fluids, GCs, IVIg | Recovery |

| Matheny et al. [1] | 68 | F | Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen) | First | Yes | MGUS | No | Fluids, vasopressors, GCs, antibiotics, IVIg | Fatal |

| Matheny et al. [1] | 46 | F | mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) | First | Yes | No | No | Fluids, vasopressors, antibiotics, GCs | Recovery |

| Matheny et al. [1] | 36 | M | BNT162b2 (mRNA) (Pfizer-BioNTech) | Second | No | No | Status epilepticus | Fluids, anticonvulsants, vasopressors, antibiotics, GCs | Recovery |

| Robichaud et al. [3] | 66 | M | ChAdOx1 nCOV-19 (Oxford – AstraZeneca) | First | Likely | MGUS IgG Kappa | No | Supportive care at ICU | Recovery |

| Yatsuzuka et al. [6] | 65 | M | BNT162b2 (mRNA) (Pfizer-BioNTech) | Second | No | No | Generalized pustular psoriasis treated with infliximab | GCs, secukinumab | Recovery |