Introduction

Biologic therapy already has a well-established position in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as reflected in recent EULAR recommendations [1]. The advent of anifrolumab (ANI), which inhibits inflammation induced by type 1 interferon pathways, is one of the first therapies to affect the pathomechanism of SLE. Type 1 interferons play a critical role in disease progression, and interferon gene signatures are activated in about 80% of SLE patients [2]. Registration studies have proven that, in addition to remission, ANI allows rapid reduction of glucocorticoid (GCS) doses [3]. For these reasons, ANI is an attractive therapeutic option in patients who cannot achieve remission with available immunosuppressive drugs and have complications from systemic GCS use. The length of therapy and post-therapy management remains an open question. In this report, we present the efficacy and safety of ANI therapy in the first 18-year-old patient outside of a clinical trial, and his follow-up, 14 months after its completion.

Case report

An 18-year-old man with long-standing, refractory SLE came to the department of rheumatology in moderate condition in April 2022 due to experiencing another exacerbation. Systemic (fever), immune (high anti-dsDNA antibodies), hematologic (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, autoimmune anemia), and skin-mucosal (oral ulcers) domains were involved (Table 1). The SLEDAI 2K value at admission was 19 points. The Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score was 2.3. The SLICC/ACR Damage Index was 1 (pericarditis). Physical examination revealed underweight (body mass index [BMI] 18.1), ulcers in the mouth and nasal mucosa, pain and swelling in the elbow, knee, wrist, ankle and hand joints (metacarpophalangeal [MCP] 2.3), and a rash on the face and forearms (Fig. 1). Auscultatorily a pericardial friction murmur was audible.

Table 1

Baseline assessment of disease activity before treatment (04.2022)

Fig. 1

A) Patient before treatment with anifrolumab. B) Patient’s response to treatment – month 1. C) Patient’s response to treatment – month 2. Source: author’s own archives, photos presented with permission of patient

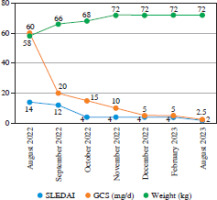

The diagnosis of SLE was established at the age of 10. Since then, the patient has been hospitalized several times for exacerbations in multiple domains, with SLEDAI 2K scale activity of 14-24 points. In 2018, central nervous system involvement (neurotoxicity) was confirmed. Exacerbations occurred despite combined immunosuppressive therapy: methylprednisolone (4-8 mg/day), azathioprine 150 mg/day, and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day), which after many years proved to be the best tolerated. It is possible that the patient discontinued treatment on his own due to poor tolerance of glucocorticoids, their current and expected side effects. No other causes of exacerbations are known. The patient did not use stimulants, physiological activities were normal, but the man did not use regular photoprotection. There was no family history of systemic diseases. The patient responded well to pulses of methylprednisolone (0.5-1.0 g/day for 3 days), but symptoms recurred every few months from 2021. Due to frequent exacerbations, steroid dependence, current and potential complications of the therapy, and the patient’s reluctance to use GCSs, it was decided to start ANI therapy under Rescue Drug Technology Access (RDTL) therapy. In August 2022, ANI was started at a dose of 300 mg by infusion, every 4 weeks. A rapid clinical response was achieved in all domains as early as 4 weeks after the first dose of the drug (Table 2). Laboratory parameters (morphology, C3, C4 complement) were normalized, and anti-dsDNA levels dropped by 57% in the 4th month of therapy. During treatment, the dose of GCS was rapidly reduced to 2.5 mg of prednisone per day (Fig. 2). All criteria for remission according to the Definition Of Remission In SLE (DORIS) [4] were achieved. The treatment was well tolerated. No significant side effects were observed. During the 12 months of therapy, the patient had 2 upper respiratory tract infections treated symptomatically. In August 2023, ANI therapy was discontinued due to loss of access to the drug, resulting from a change in the government RDTL program.

Table 2

Patient response to treatment (08.2022-08.2023)

Fig. 2

Decrease in disease activity according to SLEDAI 2K, reduction in GCS dose and increase in body weight during ANI treatment

Since then, the patient has been taking hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/day and azathioprine 150 mg/day. Despite the end of ANI treatment, the patient has remained in remission for 14 months. This is also the longest period without prednisone use since the diagnosis of the disease.

Discussion

Anifrolumab used at a dose of 300 mg every 4 weeks proved to be effective and well tolerated, allowing for rapid remission according to DORIS. Particular improvements were observed in the cutaneous-mucosal, joint-muscular and hematologic domains. This was consistent with the published safety and efficacy assessment of ANI in the randomized, registrational clinical trials of MUSE and TULIP-1 and TULIP-2 [5]. The indication for therapy in our patient was the ineffectiveness of previous various immunosuppressive therapies and the need for high doses of GCS. In addition to clinical remission, a sustained reduction in the dose of GCS to 2.5 mg of prednisone was achieved, followed by their complete withdrawal. In our case, this effect persists 14 months after the end of treatment. When we started therapy, there were no eligibility guidelines for ANI treatment, only data from registration studies. The recommendations were published in October 2023 as the Update of the EULAR Guidelines for the Treatment of SLE [2]. The strength of these recommendations is very high. The inclusion of ANI in refractory or steroid-dependent SLE is category 1A. The use of methotrexate (MTX), or azathioprine (AZA) in these recommendations is rated lower: 1B and 2B. ANI can be used in all patients, even in mild lupus as a second-line drug, and is, along with belimumab, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), and GCS, the drug that gives sustained and complete remission [2]. With classical treatment, the goal of complete remission and its maintenance > 1 year can be achieved in 40-50% of Caucasian patients. However, only 20% of patients maintain this condition for 5 years. It is known that prolonged maintenance of a low-level disease activity state (LLDAS) or complete remission according to DORIS significantly reduces the risk of permanent damage [6]. In the case of anifrolumab, there are no publications (other than registration studies) on how long to use the treatment and the risk of relapse after its withdrawal. In our case, withdrawal was dictated by a change in government regulations and loss of access to the drug. The persistence of remission after relatively short treatment (12 months) may be another, previously undescribed, feature that distinguishes childhood and adolescent lupus from adult lupus [7].

Data collected so far indicate that ANI should be considered in three clinical situations: lack of remission on standard treatment, intolerance of it, and the need for chronic use of moderate or high doses of GCSs. The reason for the latter phenomenon is explained by the fact that GCSs used in low to moderate doses do not affect interferon-induced gene signatures. Such an effect was observed for doses above 25 mg/day of prednisolone and intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone [8, 9]. The need for long-term use of systemic ICS is particularly dangerous in young patients, as in our case. This is of particular importance due to skeletal development, sexual maturation, and the risk of glaucoma, cataracts and diabetes. It has been unequivocally proven that plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which are the main producers of type I interferon (IFN), play a decisive role in the pathogenesis of SLE. IFN stimulates B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, NK lymphocytes, and neutrophils to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, contributing to the development and maintenance of SLE [10]. As a fully human monoclonal antibody that blocks IFN receptors (IFNAR1), ANI inhibits the pro-inflammatory cytokine pathway. Potential safety concerns associated with IFNAR blockade, such as opportunistic infections, viral infections (including EBV and CMV reactivation) and malignancies, have been investigated. In the TULIP 1 and 2 trials, the incidence of serious non-opportunistic infections was similar between treatment groups: 4.8% in the anifrolumab group and 5.6% in the placebo group [5]. Only a higher incidence of hemiplegia was confirmed (6.1% vs. 1.3% in the placebo group), but this was not the reason for discontinuing treatment and excluding the patient from the trial. The baseline risk of hemiplegia is four times higher in patients with SLE than in the general population [11]. For this reason, EULAR recommends prophylactic vaccination for this indication [2].

Ultimately, ANI therapy proved to be effective and well tolerated, and allowed discontinuation of GCSs, which were perceived by the patient and his parents as dangerous. The most difficult decision of ANI therapy to continue or discontinue treatment was made for us by the legislature, which changed the regulations on access to the drug. Fourteen months after completing one year of ANI treatment, the patient is still in remission and not taking GCSs.

Patient perspective

The patient and his family were satisfied with the treatment and expressed their willingness to follow up for a long time. Losing access to treatment after 12 months was stressful for the family, as they feared a relapse. The patient considered the greatest success of the treatment to be the long-term remission, during which fatigue and difficulty concentrating disappeared. The man returned to school and amateur sports, passed his high school diploma and entered engineering studies. Equally important was the discontinuation of GCSs, the actual and expected side effects of which caused concern for the entire family, especially his sister, a medical student.